THE BLOG

CEO Not (Necessarily) Required

By: Tim Cynova // Published: May 15, 2018

An Early Look Into Fractured Atlas’s Shared Leadership Model

Preamble

Those playing along at home will recall that Fractured Atlas recently embarked on a few new adventures. One of which is the creation of a four-person, non-hierarchical leadership team for the organization. (I recently shared a collection of research on the topic. If you can wait a bit longer, I’m publishing a subsequent post that distills the key findings from the hundreds of hours I spent reviewing material.)

At Fractured Atlas, we’re approaching our foray into shared leadership much like anything we attempt: as an iterative process that progresses through our R&D pipeline. This process began with deep conversations over several months between the senior leadership of our staff and board. These conversations allowed us space and time to question conventional and received wisdom, and explore questions like:

What is the role of an organization’s leader?

Why is an organization typically structured as a hierarchy with one person at the top?

What are the advantages and disadvantages of hierarchical structures?

Is there a way to use this CEO transition as an opportunity to experiment with a leadership structure that might be more in line with our anti-racism, anti-bias, and anti-oppression work?

Could we develop this while also experimenting with more organically self-forming teams? Perhaps an entirely geographically-disbursed organization?

Can this be accomplished without creating a “first among equals” on the team, or accidentally making the Board Chair the de facto CEO of the organization?

Can we be as innovative with our leadership and team structures as we aim to be when creating tools to help our amazing members?

Maybe.

The announcement that we were exploring a four-person, non-hierarchical leadership model at Fractured Atlas sparked quite a lot of interest. Some of that interest was admittedly accompanied by arched eyebrows and a skeptical “Oh, REEEEAALLLLY,” but almost universally people were curious to learn more about how the experience unfolded. What follows is a snapshot of where we are right now — an “interim report,” if you will — with an important caveat that where we are right now is constantly evolving.

How did we get here again?

On March 1, 2017, when Fractured Atlas founder and Chief Executive Officer Adam Huttler began his “non-battical,” the four senior leaders of Fractured Atlas began operating as a four-person leadership team. Over the subsequent year, until Adam’s departure from Fractured Atlas on December 31, 2017, this group coordinated strategy and tactics for the four “departments” of Fractured Atlas: Programs, Engineering, External Relations, and Finance/People/Operations (FinPOps).

At its October 2017 meeting, anticipating the departure of Adam Huttler as CEO of Fractured Atlas to become CEO of Exponential Creativity Ventures, the Board of Directors approved a one-year trial of a four-person, non-hierarchical leadership team to begin in January 2018. Titles for the four positions were equalized at the “C-level”, reinforcing the non-hierarchical nature of the team.

Why try this instead of launching a search for a new CEO?

Fractured Atlas is in the middle of a multi-year strategic initiative, shaped by the members of the Leadership Team and Adam Huttler. It would very likely slow the momentum of this plan to conduct a search and introduce a new, single leader into the organization at this time.

A non-hierarchical, shared leadership model helps advance the anti-racism and anti-oppression (ARAO) values Fractured Atlas is committed to. Hierarchical models imply that one person heads the organization and makes the ultimate decisions. A shared leadership model demonstrates a different, inclusive approach that is more in line with our stated ARAO values and fosters a diversity of voices, perspectives, and skills necessary for the organization to be healthy, well-informed, and successful.

Using a shared leadership team model lessens the organization’s dependence on any one person, and strengthens strategic thinking and decision-making capacity across a broader range of staff members.

Shared leadership models are nothing new and are commonplace in many arts organizations that have both an artistic and executive leader. There are examples of successful shared leadership models — as well as failed attempts — dating back thousands of years. The Leadership Team is studying a range of examples and is working to leverage learnings from those examples to construct the model that fits Fractured Atlas. I’ve been designated as the team’s point person on gathering and sharing relevant research and case studies (and recently spent my annual Think Week with a treasure trove of material on shared leadership, the role of the CEO, and global virtual teams). This is an ongoing conversation in the Leadership Team meetings.

Experimenting with a shared leadership model demonstrates Fractured Atlas’s willingness to question conventional wisdom and embrace challenge when we think it will offer leadership to the sector and produce better results for those we serve. Through sharing about our experiment with a four-person leadership team, we expect to be able to help a host of teams and organizations operate more effectively and efficiently in service to their missions and the field.

What exactly is being shared?

Four people collaborate to fulfill what is commonly considered the CEO function of the organization, which includes overall strategic planning, fundraising, program development, and technical and organizational management.

Fractured Atlas Leadership Team 2018: Lauren Ruffin (top left), Tim Cynova (top right), Shawn Anderson (bottom left), Pallavi Sharma (bottom right)

How is the Leadership Team structured?

The shared leadership team includes Shawn Anderson (Chief Technology Officer) who oversees Software Engineering, Tim Cynova (Chief Operating Officer) who oversees Finance, People, and Operations (FinPOps); Lauren Ruffin (Chief External Relations Officer) who oversees Development, Marketing, and Outreach; and Pallavi Sharma (Chief Program Officer) who oversees the largest team delivering our core Programs and Services.

How often does the group meet and communicate?

Important Note: Fractured Atlas’s four-person leadership team is entirely geographically disbursed. All four members live and work in different states: Lauren (New Mexico), Pallavi (New Jersey), Shawn (Colorado), and Tim (New York). This means they only see each other in 3D a handful of times each year. It requires them to be mindful of how they communicate and create alignment within the leadership team and the organization since they aren’t all sitting near each other in HQ on a daily basis.

In the year of Adam’s non-battical, the Leadership Team refined their decision-making processes, which now include: Weekly “tactical” sessions where the group reviews weekly activities and metrics, and resolves tactical obstacles and issues; Monthly strategy meetings where critical issues affecting long-term success are discussed, analyzed, brainstormed and/or decided; Quarterly two-day offsites to review strategy, competitive landscape, industry trends, and team and organizational development; Ongoing Flowdock exchanges, Zoom calls, and emails; a monthlymeeting with the Finance team to review budget and financial management reports; and other team meetings where Leadership Team members attend as appropriate (e.g., product development meetings between Engineering and Programs will include Shawn and Pallavi but not Lauren and Tim).

In addition, the Leadership Team spends an entire week in March, during the annual All Hands staff retreat, working in person with each other and the various organizational teams.

The Leadership Team meets by video with the Board’s Executive Committee on a monthly basis and on a quarterly basis with the full Board of Directors (January, April, July, and October).

How does the Leadership Team set strategy and create plans?

The Leadership Team sets overarching strategy and creates plans to execute that strategy through their monthly Strategy meetings and the annual budget process.

The overarching strategy is then made more concrete and practical through the development of quarterly, organization-wide Objectives & Key Results (OKRs) creating transparency and alignment with every team and individual staff member.

The OKRs are monitored closely on a monthly basis. As external conditions shift or barriers to implementing the OKRs emerge, the Leadership Team discusses these developments in their Strategy and tactical meetings and determines necessary adjustments.

What if the Leadership Team deadlocks on a decision?

A shared leadership team doesn’t mean that the group votes on every decision, or requires consensus on every matter. Each member functions as the CEO of their department, possesses a deep domain expertise over the related content, and is responsible for seeing that their operations support the agreed upon vision and strategy of Fractured Atlas. Where functions overlap, or where group agreement is necessary for success, more discussion is necessary and joint agreement is desired.

The Leadership Team operates to take everyone’s concerns into account, and ensure that all team members feel heard and understood. However, one of the hallmarks of high performing teams is an ability to engage in healthy conflict and resolve differences productively.

When managing conflict, the Leadership Team distinguishes between decisions of significance that impact the entire organization and ones that are more tactical. The Leadership Team practices “Disagree & Commit” for both varieties of decisions, but allows different amounts of time and weighting of votes depending on the decision’s nature. If, after healthy discussion and an appropriate time period for reflection, there are still differences of opinion about a matter, the “Disagree & Commit” principle is invoked.

In the event that the group can’t reach agreement on a decision of significance that impacts the entire organization, the team will present this matter to the Chair, who will decide with the Leadership Team if this is an issue to discuss with the Board’s Executive Committee.

How is the Leadership Team evaluated?

The annual self-assessment process for all staff at Fractured Atlas takes place during July and August. In the past, the Fractured Atlas CEO completed his self-assessment relative to explicit OKR goals and organizational strategy, the Chair of the Board canvassed Board members for input, and the Chair and the CEO discussed performance and future goals.

Informed by our ongoing research on shared leadership models, the Leadership Team is discussing the best approach to assessment in the shared model. Questions being considered include: How to best assess individual members relative to their own goals — is this limited to each person assessing themselves, or are the other members of the Leadership Team offering input? How should we assess Leadership Team members’ contributions to the Leadership Team? Are non-Leadership Team members of the Fractured Atlas staff involved in assessing the Leadership Team through a 360-degree review process? How should the Board participate in the assessment process?

What if a member of the Leadership Team needs to be reprimanded or terminated?

One of the key traits of high-performing, non-hierarchical teams is the ability for team members, and their coworkers across the organization, to hold each other accountable for their responsibilities and commitments. At Fractured Atlas, the transparent OKR process means that everyone in the organization knows every other staff member’s quarterly priorities, and how well each is doing in achieving those goals.

Holding each other accountable starts first with the members of the Leadership Team working to surface and address any concerns among themselves. If concerns can’t be resolved, then it will be brought to the attention of the Chair and, if necessary, to the Board’s Executive Committee to determine an appropriate action.

What happens when someone inevitably leaves the Leadership Team?

When a member of the Leadership Team leaves the organization, the remaining members of the Leadership Team will assess the role, determine if anything in the job description needs to be adjusted before launching a search, seek input from the Executive Committee, set out a plan and process, and then search for a replacement.

Given the importance of the members of the Leadership Team, and that the Board of Directors officially hires and fires members of the Leadership Team, it is likely that one or more Board members will be involved in interviewing and making final recommendations about the replacement.

Once the person is hired, the hard work of rebuilding the team with the new configuration begins. (More on this when further research is distilled.)

Who do Board members contact for questions, concerns, and to share their thoughts?

For matters specific to Programs, Engineering, External Relations, or People/Operations/Finance (FinPOps), Board members email the respective lead.

For matters relevant to the entire leadership team, or if it’s unclear who is best to field the inquiry, Board members email the leadership team’s group email. All four members of the leadership team receive emails to that address, and the appropriate member responds.

For meta-level or highly sensitive issues, Board members contact the Board Chair who can discuss it individually with a specific team member or as a group by adding a discussion item to the Executive Committee’s monthly meeting agenda.

This article isn’t meant to make you think that we have it all figured out — far from it — or that we didn’t approach this with concerns. We have our concerns, and discussed many in great detail, but think they are worth the risk. Healthy concerns are a part of innovation but they shouldn’t stifle innovation. If we waited on the sidelines until all of the concerns were resolved, we’d never risk and learn.

Risk aversion is a regret premium. A fee paid to avoid regret.

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

Think Week ’18: Shared Leadership Models

Photo by Oliver Fluck. (Image unfortunately does not represent the setting of my actual think week, which is more along the lines of small apartment in New York City.)

By: Tim Cynova // Published: March 30, 2018

I’m going off-the-grid for a sorta annual Think Week. On the docket for this year: process and distill learning from material related to non-hierarchical, shared leadership teams, the role of the CEO, and — if I have time (fingers crossed) — global virtual teams.

Many years ago, I became fascinated with the Think Week concept after hearing about how Bill Gates went into the woods for a week each year with a giant stack of reading material. I’ve been fortunate during my nine years at Fractured Atlas to be at a place — with stellar and encouraging coworkers — that supports similar kinds of exploration and knowledge acquisition adventures.

I’m in the process of writing a piece about Fractured Atlas’s journey with non-hierarchical, shared leadership models that we originally announced in this post. Meanwhile, I thought that I would share some of the content on the docket for next week. Stay tuned and see you on the other side.

The Secret Life of C.E.O.s [podcast]

Self-Managing Organizations: Exploring the Limits of Less-Hierarchical Organizing

Nobody’s Looking at You: Eileen Fisher and the art of understatement

The shadow of history: Situated dynamics of trust in dual executive leadership

Impact of dual executive leadership dynamics in creative organizations

Shared Leadership in Teams: An Investigation of Antecedent Conditions and Performance

The shared leadership of teams: A meta-analysis of proximal, distal, and moderating relationships

Reinventing Organizations [book]

Changing on the Job: Developing Leaders for a Complex World [book]

The Starfish and the Spider: The Unstoppable Power of Leaderless Organizations [book]

WorkLife with Adam Grant [podcast]

The virtues of hierarchy, structure and temporary teams [podcast]

Hierarchy is Good. Hierarchy is Essential. And Less Isn’t Always Better.

The dynamics of shared leadership: building trust and enhancing performance

A Meta-Analysis of Different Forms of Shared Leadership–Team Performance Relations

The shared leadership of teams: A meta-analysis of proximal, distal, and moderating relationships

Out of Sight, Out of Sync : Understanding Conflict in Distributed Teams

How Task and Person Conflict Shape the Role of Positive Interdependence in Management Teams

Shared Leadership: Reframing the Hows and Whys of Leadership [book]

Share, Don’t Take the Lead [book]

Alternative Approaches for Studying Shared and Distributed Leadership

What other content on these topics should I be exploring?

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

Scarcity and the Non-Profit People Paradox

By: Tim Cynova // Published: December 21, 2017

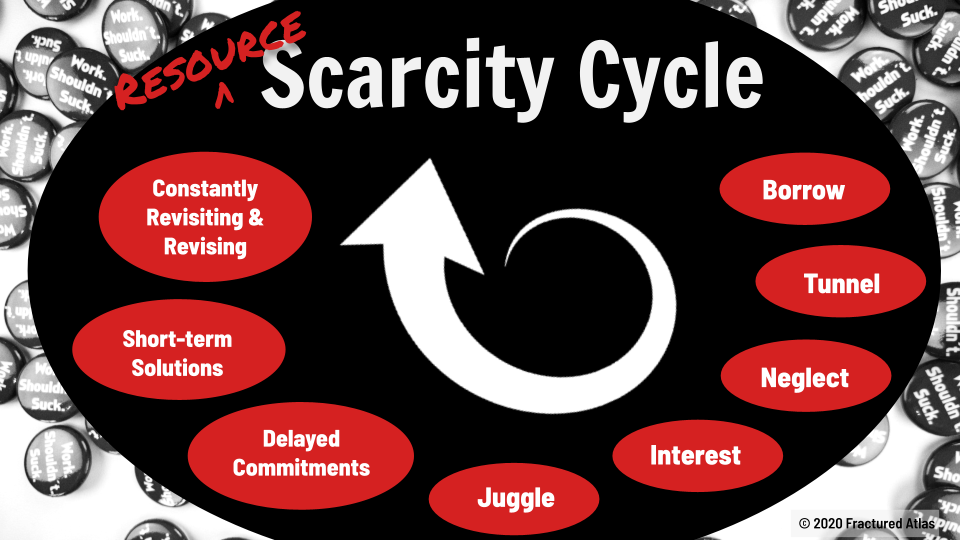

Resource scarcity leads us to borrow, and that pushes us deeper into scarcity. Why? Because when we have scarce resources we tunnel (i.e., we focus on the here and now, the fires, what needs to get done right now). Tunneling leads us to neglect. Tunneling today creates more tunneling tomorrow, and leads us to borrow — in a borrowing from Petra to pay Paula and eventually needing to pay back Petra with significant interest scenario — so that we’re using the same physical resources less effectively, placing us one step behind.

Then, we find ourselves needing to juggle. This creates a patchwork of delayed commitments and short-term solutions that need to be constantly revisited and revised. We don’t have bandwidth to plan a way out of the trap and, when we make a plan, we don’t have the bandwidth needed to resist temptations and persist. The lack of slack and capacity reduces our ability to absorb and weather shocks, and when we do have slack we use it to catch our breath rather than use those moments of abundance to create buffers against future scarcity.

Sound familiar? That’s the scarcity trap as paraphrased from the thought-provoking book Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir.

How Does The Scarcity Trap Relate to Prioritizing People Ops?

When we tunnel on the urgent — things like making payroll, or getting people to purchase tickets to our events, or reaching our crowdfunding campaign goal, or producing the annual gala to raise funds… to make payroll and present our events — we often do so at the expense of the important, bigger picture, and without regard to the impact on our people and the opportunity costs such focus exacts on our organizations.

Instead, when we focus on prioritizing people, and their capacity relative to our other institutional concerns, we unlock a powerful force and leverage our competitive advantage. So, how much time, money, and slack would you need before you pushed People Ops to the number one thing on your list? And when contemplating that answer, take a moment to consider that our people *are* our organizations.

Prioritizing people — and an organizational culture that allows them to succeed and thrive — creates your competitive advantage.

In not prioritizing People Ops — effectively punting it for another day — you’re borrowing against them and won’t develop the systems to weather scarcity. If we only prioritize people when needing to hire them, we won’t attract and retain the level of talent needed for our organizations to build necessary slack, innovate, and change the world. We’re never going to have the resources to save ourselves. Why?

Most of us believe we’re working smarter not harder. The fact is though, we’re caught in scarcity’s flywheel and it’s cascading a fire fighting, scarcity mindset throughout our organizations, magnifying the problem as things become worse for everyone. We’ll never “catch up.” Worst of all, we’re often oblivious to what will help us out of the bind as we focus on the fires, or assume if we just score that big grant — come onnnnn, lucky major foundation grant! — or sell out our season, we’ll finally be able to get ahead.

Studies show that when our resources are scarce, we’re preoccupied by that scarcity. That preoccupation negatively impacts our intelligence. In side-by-side tests, when we’re distracted by our scarce resources, we perform worse on tests than when answering the same questions when not under resource pressures. (The difference is upwards of a 13-point dip in our IQ!)

Tunneling Tax

Our sector’s common refrain — or badge of honor, depending on how one views it — is that since we’ve been operating with scarce resources for years, we’re skilled at operating under these pressures. Well, maybe. Here’s another research finding: Experience in scarcity makes people better at operating with scarce resources, *but* it also creates tunneling and the related negative consequences. Tunneling responses — increasing work hours, working harder, foregoing vacations — ignore the long-term consequences of these actions.

We introduce quick fixes and patches that come back to haunt us. It’s like purchasing a cheaper washing machine that breaks down more frequently. Putting off a more important task for an urgent one — because we’re tunneling — is like borrowing at high interest. It might address an immediate need but, like that cheaper washing machine, it’s going to come back to haunt us, and require more of us, before we know it.

To deal with the future, we need bandwidth, but scarcity’s bandwidth tax means we can only focus on the here and now. And even when we’re lucky enough to have bandwidth, it can have surprising effects.

And when we get back to the start, we have fewer resources and are farther behind.

When Building Slack Feels Counterintuitive

When you’re already busy, and trying to cram even more stuff into your schedule, the tools to build slack feels counterintuitive. Rather than trying to cram everything into a packed schedule — I just need more time! — building in slack increases our ability to get things done. (Don’t believe me? Read the illuminating Example 2 below.)

What does this mean for us in the cultural sector? Sometimes there’s a way to solve a perennial challenge that runs counter to conventional wisdom. Sometimes it’s not about needing more money or more people.

Thought experiment: At a recent conference, I heard a speaker say, “In our overworked, under-resourced organizations, how are we supposed to make progress?” Well, what would it look like if our “overworked” and “under-resourced” organizations had exactly the same resources but weren’t overworked, delivered on their missions, and changed the world?

What would it look like if your Development Associate wasn’t slammed wall-to-wall with more work than could be accomplished during an eight-hour day. What if they had flexibility in their schedule? How could that slack help your Director of Development and development department be better able to execute their work (and when I say “work,” I’m also including time to think, dream, and experiment).

When you manage bandwidth and not hours, you start to see other benefits. Henry Ford is credited with popularizing the standard five-day, 40-hour work week. It wasn’t that he was benevolent. It was that he recognized it made workers more productive during their “on” hours because they were healthier, more focused, and made fewer mistakes.

What Can I Do About This?

First, focus on your people: what you are asking of them, the environment in which you’re asking them to do it, and the type of support and feedback they receive. Focus on building diverse teams that level up and break through in ways that homogeneous teams can’t. If everyone has the same relative background and experience, even if you have a moment to consider how to deploy resources if you didn’t do an annual gala, you’re less likely to end up with innovative alternatives.

Second, you can’t do everything and need to make tough choices about what can be accomplished. Again, what would it look like if overworked and under-resourced organizations had exactly the same resources but weren’t overworked and didn’t feel under-resourced? It likely would mean they’d have to make tough, probably painful, choices to consciously *not* do things they love. It’s like pruning your prized plant so it can grow and be healthier.

If you say, “We don’t have the resources to accomplish everything we need to do,” than you’re trying to do too much. You might reeeeaaaaaally love that thing, but if it’s undermining your ability to deliver on your mission without burning the place to the ground, you need to take it off the list. You need to stop doing it. Quality over quantity here. (See also: Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.)

Lastly, once you’ve pruned and protected, get ready to lean in when you have periods of slack and abundance. It’s counterintuitive, I know. “I just need a break and a breather” is often the natural inclination. Kicking yourself into a higher gear when you have periods of abundance — and determining ways to smooth out the ebbs and flows — will enable you to bank slack for the future.

Can You Help Me Out Here?

Want to level up your People Ops to create more periods of slack and resilience? Here’s an extensive list of People Ops resources covering a whole host of topics. Want to chat about this or another People Ops challenge that’s on your mind? Connect for free HR assistance and ping me at hrhour@fracturedatlas.org.

Special thanks to my coworker Lauren Ruffin who introduced me to the resource scarcity research through this article that set me on this path of discovery, a journey that further solidifies my resolve that strategic People Ops are key to helping us address the challenges we face in the cultural sector.

Extra Credit: Illuminating Real Life Examples

Example 1: Chennai, India

One research study cited in Scarcity followed street vendors in Chennai, India. These vendors earn $1/day and take loans to buy their goods that charge interest rates of 5% daily.

The study divided people into two groups. The first group operated as usual: in debt, earning $1/day, and borrowing money at 5% daily interest to pay for their goods to sell. The second group was given a one-time infusion of cash to pay off their debts and break free from the trap. The researchers then tracked the two groups for a year. What happened?

Within a year, all the vendors were back in the same place, in debt, living on $1/day, and needing to take loans with 5% daily interest. Why? While they momentarily had bandwidth and slack, they didn’t have enough slack to weather the hits that would come along the way: buying school clothes and supplies for their children; unexpected medical bills for themselves and their family; and so on.

The Indian street merchant study offers a powerful, and sobering, example to those of us in organizations who “just need that one grant to finally have room to breathe.” “If we can just secure the $100,000 grant, we’ll be able to get ahead of the curve.” Even if we get it, we’ll likely find ourselves right back where we started.

Example 2: St. John’s Regional Health Center

When we’re tightly packed, we reduce slack. St. John’s Regional Health Center performed upwards of 30,000 surgical procedures a year in 32 operating rooms that were always fully booked. Staff were performing surgeries at 2AM, waiting hours for an open room, working unplanned overtime. “The hospital was like the over-committed person who finds that tasks take too long, in part because the person is over-committed and can’t imagine taking on the additional — and time-consuming — task of stepping back and reorganizing.”

The hospital would start the week with its operating room schedule. Before they could even get going, emergency surgeries would crop up that would bump elective surgeries, and then those elective surgeries would bump other elective surgeries later into the week until more emergency surgeries bumped those, and pretty soon people were operating late into the night and on the weekends. Knowing surgeries would likely be bumped, surgical teams would schedule all of the elective surgeries early in the week, which caused further bumping when the surgeries actually were bumped… which caused more bumping. This led to the teams being more exhausted, unhappy, and a general feeling that, “if we only had more operating rooms we could get this back on schedule.” (Sound familiar to resource constraints in your organization? If we only had x, y, z.) So, what did the hospital end up trying?

They realized that while a percentage of the surgeries were emergencies and were unplanned, they weren’t *unexpected.* The same thing happened every week. Here’s where a bold, counterintuitive approach came into play. The hospital took one of its operating rooms offline and allowed it to be used *only* for those unplanned, but not unexpected, surgeries. Everything else needed to be scheduled in the other operating rooms. As you can imagine, this move went over splendidly. Well no, people were furious, “How could you take away an already precious resource!?!?! We don’t need fewer rooms, we need more!!”

What they found was that with one operating room set aside for unplanned surgeries, the other surgeries weren’t being bumped as frequently. This in turn allowed teams to more confidently schedule elective surgeries for later in the week without fear that they’d roll into the late night or weekend. This evened out the schedule, reduced the long work hours and weekend surgeries, resulting in more focused teams that made fewer mistakes, and people feeling less stressed and unhappy. Voilà!

Example 3: New Jersey Transit

Those who ride the rails on a regular basis are well aware of this classic example. If there’s little to no slack in a system, then any train delay forces all the trains behind that one to be late as well. It’s impossible to “catch up” by leaving the station early. You can lose time, but never gain it back. Minor delays therefore pile up and quickly turn into major delays on a regular basis. (Example provided by my friend whose commute on NJ Transit provides him with daily reminders of why slack in systems is so important.)

Example 4: Slack vs. Fat

Corporate cost-cutting in the latter part of the 20th century famously resulted in “right sizing” and cutting “fat” out of companies. “Oh, you have an assistant who has work to fill about a third of the day? Well, now you share that assistant with two other people.” On the face this appears to make sense. Counterintuitively though, this created unintended cascading scarcity trap issues. Now the assistant had a full day’s worth of work but lacked bandwidth to help when something urgent arose. This meant that the urgent bumped the important with cascading effects to the three people they worked with and beyond.

Congratulations! You’ve completed the extra credit portion of this piece.

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

Work. Shouldn’t. Suck.: Why People Ops Can’t Wait Until Tomorrow

By: Tim Cynova // Published: November 22, 2017

This piece details a core belief of mine, and why, especially if you’re a leader in the cultural sector, I believe you should share it too.

Strategic HR — or People Operations — is a senior-level management competency that needs to be embedded in every decision we make in our organizations.

Why do we need to think strategically about our People Operations and embed it in everything? Why can’t we just give it to the “HR person”? Well, because this, for one reason:

Gallup’s Worker Engagement Index found that, globally, only 15% of employees are engaged. Engaged employees are those with passion and who feel a profound connection to their company. They drive innovation and move the organization forward.

15% Engaged - 60% Disengaged - 25% Actively Disengaged = Not Great News

That leaves a whopping 85% of employees who are not engaged. Sixty percent of total employees are disengaged and essentially checked out. They’re sleepwalking through their workday putting time — but not energy or passion — into their work. And then there’s… wait for it… 25% of total employees who are *actively* disengaged — WOWZA!! That’s a quarter of employees who aren’t just unhappy at work, they’re busy acting out their unhappiness. Every day, these employees undermine what the 15% of engaged coworkers are trying to accomplish.

We have almost *double* the number of people actively working against us as working *for* us — inside our own organizations!

(I’m just going to pause to let that fun fact sink in.)

In letting this happen, we’re effectively setting a whole host of organizational resources on fire. All of those hard-fought resources you’ve been struggling to obtain and maintain? Poof, up in smoke. If you like money, think of it this way: Congratulations on receiving that $100,000 grant… minus the 85% disengagement tax… that leaves $15,000. Hope it was worth all the hard work.

Maybe those percentages are bearable if your organization has 50, or 100, employees — inertia in large organizations is a powerful force allowing some to operate incompetently for too long — but this is *catastrophic* when we consider that the vast majority of our cultural sector organizations are operating with fewer than 10 staff members. You, leader who is reading this, might be the only employee in your organization who is engaged, which means you have even more of a responsibility to do something about it.

Another gut punch

Before we explore how to use this information, here’s another fun fact: 51% of our employees are looking for another job. If by now you’re standing in a puddle of tears, I don’t mean for this news to break us down. There’s actionable intelligence we can glean from this group that can help us as we begin to approach our People Ops work more strategically. It might be painful intelligence for us to receive, but it’s necessary to move forward strategically.

Overall, the news from Gallup’s Engagement Index is slightly better for those of us working in the U.S. and Canada. Only 7 of our 10 employees are disengaged instead of 9 of the 10 globally. Even this relatively positive news though results in a kind of stalemate tug-o-war where engaged employees versus the actively disengaged employees tire each other out as they remain locked in place. In this scenario, we’re essentially betting our organizational success on our disengaged staff. (My heart goes out to cultural sector colleagues working in Britain who have 8% engagement, and Japan who have 6% engagement.)

Work shouldn’t suck.

As leaders, we are shirking a core responsibility if we allow this to happen without continually trying to do something about it. And, if after reading the statistics above, you get mad like me and say, “Damn right, work shouldn’t suck for me or anyone else,” then demand that more of our cultural organizations — organizations dedicated to making the world a better, more beautiful place — don’t do it by burning through staff.

Our organizations are chocked full of creativity, let’s harness it to create innovative workplaces — with a sense of shared purpose — where people can do their best work and thrive. That’s the *least* we can do, because doing that affords us the ability to actually change the world while treating employees with respect and humanity.

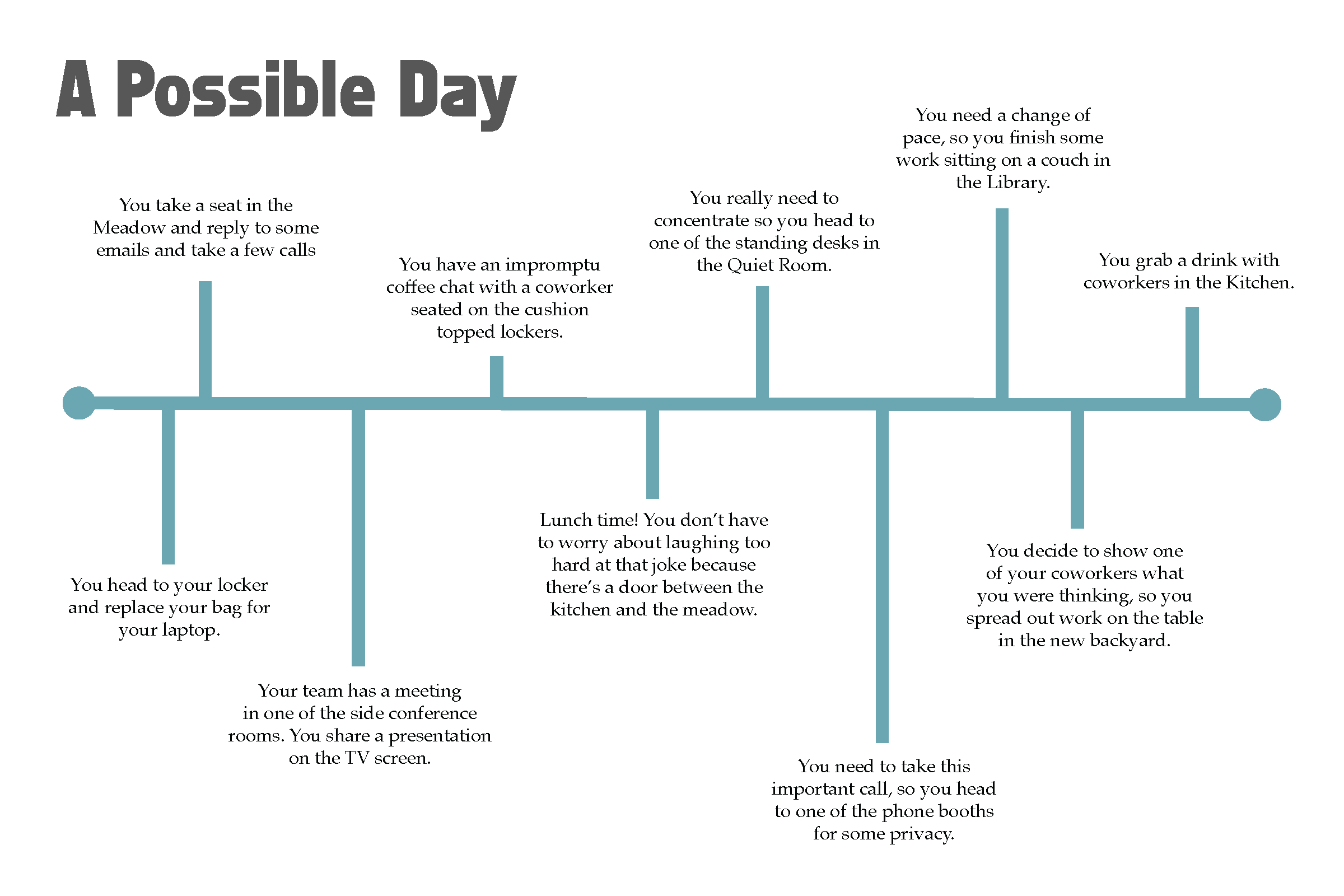

This creativity can start simply by questioning conventional wisdom and how we’ve always done things. Why do we include that educational requirement line in our job postings? Why are most of our offices essentially replicas of the ones our grandparents worked in 50 years ago? How could we work in ways that better reflect the way people live and work today? How can we demonstrate anti-racist and anti-oppression values in our workplace? When technology gives us access to billions of talented people around the world, why do we still centralize organizations? What’s the purpose of our staff meeting? Is it an effective use of the most expensive meeting our organization regularly holds? Why do we do that thing on an old computer that repeatedly transforms a 60-second process into a 20-minute struggle thereby eating up hours of staff time a week?

If, even after the above, you’re still skeptical that strategic People Ops is worth it, I’ll give you one last data point: research shows people who work in alignment with their motivators — who feel engaged in the work they’re doing — produce higher-quality work, have greater output, earn higher incomes, and are 150% more likely to live a happier life.

Not just for Executives

While my argument is mainly aimed at senior leadership and organizational decision makers, the responsibility doesn’t rest solely on their shoulders alone. People Ops, and great company culture that permeates the entire organization, isn’t possible if it’s just the Executive Director. You can lead from wherever you currently find yourself in an organization. Leaders can be separate from from managers, supervisors and executives. Some of the people in those positions aren’t leaders. And vice versa, a person on the bottom rung of a hierarchical org chart can be a culture carrier and leader within their organization and influence its trajectory more than formal leaders. With this in mind, what can we all do about the disheartening figures above that impact us all?

Start Somewhere, Anywhere

Don’t know where to start? Start by imaging a place where your most idealistic self would love to work and where you could thrive. Don’t let years of scarcity mentality and “this is how it’s done in non-profit” compromises anchor you to an environment that you merely put up with it. Even if you love your job, there are bound to be things you’d like to change that would make you more engaged. For instance, I love what we’ve built, and are building, at Fractured Atlas, but I’d still love if it was a little more Big Island of Hawai’i adjacent and/or had vistas where I could just stare across them and imagine how we can implement things to be even better.

Again, this doesn’t just need to be all on the shoulders of the organization’s leader. Making People Ops more central to an organization’s strategy and tactics involves everyone in the organization as you explore and identify things large and small. It also doesn’t have to be on level with a total office redesign. Early in my Fractured Atlas tenure, we just wanted a place to wash our lunch dishes that wasn’t the tiny sink in the tiny restroom. Small wins can sometimes make a huge impact in our level of engagement.

If you’re someone who finds yourself in the 85% of disengaged workers, might I suggest looking at Amy Wrzesniewski’s work. Amy’s research focuses on finding meaning in one’s work, and includes a job crafting toolkit to help you create the job you want from the job you have. Or, take a look at Chester Elton and Adrian Gostick’s What Motivates Me assessment. While leaders have a responsibility to help create the environment where great things can occur, we all have a responsibility to own our part of the work.

No one will care more about you and your career than you. You’re the CEO of You Inc.

If you’re stuck and feeling helpless, ask yourself, “What can I do right now to move towards what I really want?” (You have more options than you think.)

Leaders don’t set out to make work suck

Most leaders don’t set out to create and run organizations where work sucks. They, like the regular human beings they are (even if some seem larger than life), are trying to do the best with the hand that’s been dealt. Sometimes we don’t know what we don’t know and that leads us to make wrong decisions, or ones that unintentionally devalue something that has a significant impact on our organization’s ability to deliver on its mission. This isn’t surprising given the Scarcity Trap that snares many non-profit executives. This is why we need to create an environment where everyone owns People Ops, and then continually work to iterate and improve it.

For the health and future of our sector, it’s incumbent upon all of us to make people and People Ops a key consideration in everything that we do. It’s hard work, but it’s not difficult to simply start showing that you care about each other. Unlike the stalemate tug-o-war, there’s no neutral here. We’re either moving forward or falling behind and, if we choose not to engage with this, other organizations will happily eat our lunch.

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

Nix the Education/Experience Proxy

By: Tim Cynova // Published: November 16, 2017

The Education/Experience Proxy is what I call the phrase organizations include near the end of their job postings: “High School Diploma Required,” “Bachelor Degree Required,” or “Masters Degree Preferred.” Please nix it. It’s a lazy proxy used to approximate experience or ability that’s making it harder for otherwise talented people to be a part of your candidate pool. It neglects people who learn differently, or have different life experience, from being considered for positions.

We certainly don’t need an education/experience proxy in the cultural sector. You might request years of experience doing the work but shouldn’t invoke an experience proxy. Unless you’re a brain surgeon or a nuclear scientist, it seldom matters how much formal education you’ve completed.

It’s what you *do* with the knowledge you’ve acquired during your life that’s important, not the knowledge in and of itself. And no, I don’t buy the blanket, “obtaining one’s diploma demonstrates that they can see a significant, multi-year effort through to completion” argument. Yep, if they’re going to complete another degree than yes, that specific past performance might be indicative of future results. I’ve known plenty of people who did exceedingly well in school only to struggle mightily when they graduated and got a full-time job, and vice versa.

This isn’t a post railing against those who’ve had the opportunity to attend prestigious schools or against formal education itself. This is a post arguing that two 30-year-olds each take their own path in life before they end up across from you in a job interview. One might have completed a Bachelors, Masters, and Doctorate. The other might have worked every position in a marketing agency to gain their expertise, or lived all over the world working on the crew of a shipping vessel, or spent years in a cabin in the Northern reaches of Canada launching and running a successful online business.

It’s one thing to learn and another to be able to apply that learning.

I say that the educational criteria is a lazy proxy because, when we use it, we’re essentially shifting some of our selection burden to an unknown admissions officer and unknown teachers. I’m not saying it isn’t a significant accomplishment to finish high school, or get accepted to college, or graduate with one’s doctorate. I’m saying, that specific experience might not make someone successful in *your* organization and for the role you’re hiring.

I’m not an expert in a lot of things — not even about my passions: the Tour de France, bourbon, and artisanal donuts (well, maybe artisanal donuts) — but I *am* an expert in what it takes for someone to succeed at Fractured Atlas and finding people who will excel here. So why would I outsource this to someone, or some system, who doesn’t understand how 100 ingredients combine to make people successful at Fractured Atlas? And why should you?

The education/experience proxy is a hurdle standing between you and more diverse applicants applying to your company.

Here’s another thing:The education proxy is a hurdle standing between you and more diverse applicants applying to your company.Those who didn’t have certain opportunities shouldn’t be penalized for something that doesn’t matter to their ability to successfully accomplish the work and add value.

As the cultural sector, let’s make a pact right here and now. Let’s be clear about the skills necessary to successfully accomplish the job and nix the proxy criteria that isn’t relevant to people being successful. Diversity of thought and experience make our teams and organizations stronger. Let’s not make it even more challenging to accomplish that. (Search firms, I’m looking at you here too. Companies instinctively include this line in job postings. Please advise clients that the education/experience proxy is unhelpful to their end goals and makes it harder to find great people.)

Don’t mistakenly think the education/experience proxy is going to do the heavy lifting for you. It’s often a bias that causes us to miscalibrate candidates. Let’s get more strategic about our hiring. Putting the work in upfront so we improve the odds of hiring the right person, and lessen the chances we’ll be redoing the search all over in a few months, or banging our heads against the wall for months or, God help you, years trying to figure out why it’s not working out.

Resources to Help

Google’s re:Work site provides tools that can help with unbiasing and also with strategic hiring. They include straight-forward tools that can be implemented relatively fast. There’s also the terrific book, Who: The A Method for Hiring that breaks down, from start to finish, how to structure a strategic hiring process. And lastly (well, “lastly” in this post), Textio helps you draft and edit your job postings to make them more inclusive.

So please, cultural sector, let’s nix the education/experience proxy in our job postings.

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

15 Structured Learning Opportunities

By: Tim Cynova // Published: November 7, 2017

After publishing an extensive list of HR resources and announcing the launch of our Strategic HR Bootcamp in January, a colleague recently asked me where I turn for my own professional development training. Here are some of the highlights I’ve enjoyed for structured learning:

Building Competencies & Community

National Arts Strategies has partnered with business schools and leaders from around the country to create and offer high-quality learning, specifically tailored for the creative sector. I find their offerings quite helpful when filling in gaps in my own Musicology/International Affairs educational background. In the past, I’ve attended their two-day sessions on Finance, Managing People, and Strategy. Nowadays, their offerings are slightly different and include asynchronous online offerings as well. The quality is still just as high.

Tools for Tough Conversations

Fierce Conversations two-day training. Several years ago, we were exploring conversation frameworks to adopt at Fractured Atlas. We knew we needed skills to help us engage in healthy conflict and navigate challenging conversations, particularly as we started our all-staff anti-racism trainings. We looked at Crucial, Difficult, and Fierce Conversations (a cottage industry of [Fill-in-the-blank] Conversations models exists). While we ultimately went with Crucial Conversations, there’s a lot I love about Fierce. I find it’s particularly well suited for those in management roles, especially with Fierce’s frameworks to help structure delegating relationships, digging deeper into the root causes of stress and conflict, and even running effective meetings.

Crucial Conversations two-day participant session and two-day Train the Trainer, uh, training. Described by a colleague as more algorithmic than Fierce, I’m fond of CruCon (as we affectionately call it at Fractured Atlas) for its framework and use of video scenarios. Not everyone feels comfortable sharing the tough conversations they’ve had, or need to have, when skill building for tough conversations. With the video scenarios, every person can participate and learn without the stress of having to think of, and share, examples from their own life that are real, but not *too* real. Every staff member at Fractured Atlas goes through some version of the training during their tenure, and I’m excited to learn something new each time I teach a cohort.

Identifying & Aligning Motivators

The Culture Works’s What Motivates Me one-day Train-the-Trainer training introduced me to tools for identifying and aligning employee motivators, engagement, and recognition. It’s like Myers-Briggs but helps you make sense of what motivates you personally and professionally. So, you say Family is #1 — when you think a family member might be looking over your shoulder as you take the assessment — but this assessment just said you rate Family as #5 and *Fun* is actually your #1 motivator. You can even use their model to do individual or team job sculpting. (Buy the book for a code to take the assessment.) After you have your team conversation, you’ll be better equipped to align the kinds of recognition people prefer so you don’t keep giving Susan those Starbucks gift cards only to find out 10 cards in that she doesn’t drink coffee… but she loves Shake Shack (well, I mean, who doesn’t).

Artisanal Organizational Culture Tours

Zappos Insights offers a menu of opportunities to peek behind their famous company culture curtain. Several years ago, I attended their Coaching Camp (doesn’t look like they offer that specific training anymore). Their offerings might be a little too pricey for smaller non-profits, but they do offer non-profit discounts, and occasionally hold competitions for a few full scholarships for non-profit attendees (keep your eyes peeled to their Twitter feed). When I visited, we were in the early days of creating an internal coaching program at Fractured Atlas. The Zappos program provided me with tools for creating a program, and also offered a look at this company I’d admired for years. This journey also took me to The Motley Fool in Alexandria, VA where, like Zappos, you can join them for a tour of their space. It’s like a artisanal distillery tour for organizational culture.

Negotiation & Mediation

Harvard Law School’s Program on Negotiation’s 3-day Dealing with Difficult People and Problems. The agenda was packed with learning, including a memorable session with real-life hostage negotiators as well as one with those working on international peace treaties. One of the more memorable exercises from our time together focused on a cross-cultural employment negotiation. Each person had a secret list of the employment terms they would accept, and the things they could and couldn’t say. For instance, for the new employee it was bad luck in their home country to start something new on a Monday. It was preferable to start new initiatives on a Friday, but talking about the reasons was considered bad form. For the employer in a different country unfamiliar with this, they required all new staff to start work on Monday. You can see how introducing a handful of these variables could make for a challenging negotiation and unique learning experience.

The Center for Understanding in Conflict’s Basic Mediation and Conflict Resolution Training. This session is the only one listed here that I haven’t attended yet, and I’m excitedly looking forward to it in a few weeks as it was highly recommended to me by a colleague. I want some formal grounding in this area, and I’m also intrigued by their approach that recognizes the personal toll serving as a mediator can have on someone. Saying a mediator is a “neutral party” doesn’t mean the act of mediation has a neutral impact on the mediator. Will let you know how it goes.

Anti-racism & Anti-oppression

The People’s Institute for Survival and Beyond’s Undoing Racism. I had the distinct pleasure of working with Ron Chisom, a co-founder of People’s Institute, as one of the facilitators for the 3-day session I attended. If you’re earlier in your journey to understanding race and oppression, Undoing Racism introduces participants to the history of racism, institutionalized racism, power analysis, and the stages toward becoming an anti-racist organization.

Fractured Atlas staff participated in three all-day anti-oppression sessions with YK Hong last year. This year, we have anti-racism and anti-bias sessions with Keryl McCord and her team at Equity Quotient. (I’ve also enjoyed working with Tiffany Wilhelm who facilitates our monthly staff White Caucus.) The anti-racism journey for us will never be complete, nor how we can apply the learning to our organizations, so I welcome the different perspectives on the work.

HR Overview

David’s Siler’s 10-week SPHR prep course was incredibly valuable as a comprehensive overview of HR. I took this course in preparation for the SPHR certification exam, but also highly recommend it for anyone who’s coming into the People field without a formal background in HR. For a few hundred dollars you can get the self-paced materials and, as long as you can self-pace yourself, it’s nearly as good as the live course. Not convinced you can self-pace? There’s an online version and, if you live in North Carolina, Siler’s futuristic 3D option.

Digging Deeper

SHRM’s Leading Internal Investigations. The Society for Human Resource Management has an exhaustive list of courses, webinars, toolkits, and books available on their website. If you’re involved in any way with People Ops, at some point you’ll be faced with a situation that requires speed, tact, professionalism, and thoroughness. So and so said or did something, and now it’s up to you to figure out what, if anything, occurred and how to appropriately address it. This course gives you the guidance.

What trainings have you found most useful to you on your career journey?

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

In Thanks of Mentors

My mentor and friend, Steve Morris

By: Tim Cynova // Published: October 3, 2017

Over the weekend, I learned that one of my longtime mentors — Steve Morris — passed away from cancer at the end of July. Not knowing this at the time, I emailed him in August to see if he had any availability to meet up for our semi-annual breakfast this fall.

After not hearing from him, I grew concerned. Usually if he was traveling, he’d send a quick email and we’d reconnect upon his return. This wasn’t like Steve, so I Googled his name and hesitantly typed “obituary,” hoping that the search would turn up empty. Then, I sat there with tears welling up in my eyes as I saw his picture and a loving tribute. Steve Morris was my mentor and a friend for almost 15 years.

Steve didn’t come through a formal mentorship program, nor do I think I ever called him my mentor to his face. (I mean, I certainly *thanked* him, but didn’t say, “Thanks for meeting me, mentor.”) Neither did I wake up one day and say, “I need to go out and get some mentors.” Steve was a board member of mine when I was a young, idealistic (or perhaps “naive” is the appropriate word), Executive Director at The Parsons Dance Company. When I left that role, we stayed in touch. He was generous with his time and insights. He took an interest in what I was doing and the companies where I worked. And he appreciated that I would often thank him in later years with a bottle of difficult-to-locate bourbon.

Other people I consider part of my mentor crew came into my life in similar ways. Some of them include a college professor who I had for only one class but who has remained a mentor for over 20 years. A friend’s husband who worked in pharmaceuticals and shared a love of NY1 (and who himself was taken away too early by cancer). Another former board member who influenced my thinking and career trajectory by introducing me to the field of organizational psychology and the research behind finding meaning in one’s work. And a friend who I’ve had the great fortune of working with for almost nine years.

Be careful whose advice you buy, but be patient with those who supply it.

A great mentor can be with you, guiding you for the long haul. They often knew you “back when,” and help you develop into who you become. They see your struggles, and nudge you in a helpful direction every now and again. They make you think differently about things, and help you consider ideas and perspectives that don’t come naturally to you. And by and large, they have a generosity of spirit that makes them willing to do all of this in the first place.

Learning of Steve’s death caused me to reflect on some thoughts about mentors, and what makes for a fruitful partnership:

Great mentors can come from anywhere and be nearly anyone. You just need someone who is more experienced in an area.

Relationships can be bidirectional. I’ve learned quite a lot from my mentors and, in turn, taught them way more than they ever asked about the Tour de France and the differences between donuts and *artisanal* donuts.

The best mentor relationships develop over time into just that. Otherwise they’re usually called acquaintances.

Be mindful of people’s time, and take the hint if they’re not as into you as you are into them. Not every relationship was bound for a beautiful mentorship. (Uh, dear mentors of mine, please let me know if I’m not getting your hints.)

Offer to pick up the tab for coffee or breakfast, unless your tug-o-war for the check becomes too awkward to continue, then pull harder on it next time.

Consider bringing a gift of some sort to say thank you — brown spirits, red wine, or champagne are my frequent “go to” gifts; baked goods when I was earlier in my career— because, you know, it’s a token that shows you care. In lieu of, or in addition to gifts, give them a sincere and specific thank you.

Come prepared with specific challenges and questions, and don’t neglect to demonstrate an interest in *them*.

Bring a sincere interest to learn and to better yourself, to look at and question your shortcomings and blind spots, with no expectation of anything in return from your mentor except their insights. (Mentorships shouldn’t be approached as a sly way of getting a job. It will be abundantly apparent if you try.)

Give them space. One or two meaningful conversations a year are likely to be more beneficial over time than getting together on a monthly basis. Allow time for things to develop so you’ll have new, meaty material to discuss the next time around.

A mentor doesn’t need to be older than you.

Several years ago, I published twenty-five interviews with leaders from a variety of sectors. The interviews centered around how to attract and retain great people in organizations. Having lost two of the mentors who I interviewed, it now turns out to be an opportunity for me to spend a few more minutes with them, hearing their voice, and revisiting their advice. It’s also a way for me to share their insights with those who now will never meet them.

Years ago, I was having breakfast with Steve and asked him about how he managed his time in the constant battle of the urgent versus the important. He explained his simple approach that I still use to this day. Steve used his morning commute to walk through his day, thinking about the purpose of each activity and meeting, and what he needed from each. “You see, young(er) Tim Cynova, if you don’t know what you want to get out of a meeting, or your day for that matter, you’ll have a tough time knowing if, or when, you’ve ever achieved it.”

Thank you, Steve Morris, for your kindness, your insights, generosity, and caring. And thank you to all those who I’m humbled to call my mentors.

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

101 HR Thought Leaders, Books, Websites, Videos, and Courses

By: Tim Cynova // Published: September 19, 2017

What resources have you found helpful in your People practice?

Break out your Trapper Keeper, throw the Jansport strap over your shoulder, and sharpen your no.2 pencils. It’s back to school season! This post is full of resource recommendations for those looking to put a couple more HR arrows into their quiver.

Many of us in the cultural sector discover the HR or People field by accident. We land our first Executive Director position and then quickly find out there’s more to this whole People thing than posting for open positions and processing payroll.

Below is the Fractured Atlas People team’s quick guide to books, thought leaders, classes, and websites that we’ve found helpful in our own learning. The resources cover every aspect necessary to build a healthy and effective People function in your organization.

It should be obvious that if you don’t know the difference between a Balance Sheet and a Statement of Financial Position — trick question, they’re the same thing — you need to find an understanding financial statements tutorial before that call with your board treasurer to discuss the annual audit. It’s less obvious the relative importance of People operations, and where to turn when you’re having trouble hiring and retaining a diverse workforce, or building an organizational culture that can change the world, or deciding if and how to introduce remote work arrangements.

We often use conventional wisdom to help us address HR issues when, in fact, that can be some of the worst advice. (Hire with your gut? Your gut has unconscious biases.) The resources below leverage science-backed solutions to help us make sense of the vast People field.

When I say “vast,” here’s a glimpse at the subject areas one needs to master when working to obtain the field’s senior certification (a certification akin to the CPA of HR):

HR Competencies: Leadership & Navigation, Ethical Practice, Business Acumen, Consultation, Critical Evaluation, Relationship Management, Global & Cultural Effectiveness, and Communication

People: HR Strategic Planning, Talent Acquisition, Employee Engagement & Retention, Learning & Development, and Total Rewards (compensation and benefits)

Organization: Structure of the HR Function, Organizational Effectiveness & Development, Workforce Management, Employee & Labor Relations (Unionization), and Technology Management

Workplace: HR in the Global Context, Diversity & Inclusion, Risk Management, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Employment Law & Regulations

It’s a list filled with meaty topics; the stack of exam review guides alone measures over a foot high. But don’t be discouraged, pick your pain point(s) and just start learning. What follows is a set of resources to help you think and act both more tactically and strategically in your People operations pursuits.

First, start learning from these leaders in the organizational behavior, organizational psychology, and the People field:

Thought Leaders

Amy Wrzesniewski is one of my heroes and someone who greatly influenced my own People thinking and career trajectory. Her work centers around helping people create meaning in their work.

Jane Dutton, from University of Michigan’s Center for Positive Organizations, along with Amy Wrzesniewski and Justin Berg, authored the research around Job Crafting and this exercise packet.

Adam Grant is a professor at Wharton and seems to be everywhere these day, but maybe that’s just because I follow him on Twitter. Check out his research in Give and Take: Why Helping Others Drives Our Success and Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World.

Robert Sutton is a Stanford professor and author of The No Asshole Rule: Building a Civilized Workplace and Surviving One That Isn’t answering the question, “Do you need to be an asshole leader to change the world?”

Huggy Rao (co-author with the above Robert Sutton) of Scaling Up Excellence: Getting to More Without Settling for Less tackles the best way to scale organizations for the long term.

Jennifer Brown writes and thinks about inclusion and has free resources like the Diversity Starter Kit for CEOs available on her website.

Jeffrey Pfeffer another Stanford professor with research centered around building better companies by putting people first.

Angela Duckworth is the author of Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance and helps us understand why some people succeed and others fail.

Lee Burbage is leading the People team at Motley Fool and openly sharing their content so the rest of us can be inspired, and maybe borrow a thing or two.

Laszlo Bock, Google’s former Chief People Person, who recently launched Humu, literally wrote the book on Google’s science-backed People efforts, Work Rules! Insights from Inside Google That Will Transform How Your Live and Lead.

Vivienne Ming is a theoretical neuroscientist motivated to maximize human potential.

Top 100 HR Influencers of 2017 compiled by Engagedly. Comb the list to add new thought leaders to your social media feeds. One of my frequent follow on the list is Tim Sackett, because we share a first name, Midwestern roots, and an affinity for Shake Shack and Cinnabon.

Websites

Google’s re:Work offers a wealth of tools based on their research. Topics cover Hiring, Goal Setting, Managers, Teams, and Unbiasing.

Fistful of Talent is a talent management blog started by Kris Dunn with a host of voices featured in its content.

Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) is a great resource. With an annual membership you gain access to countless articles and templates. They also have a variety of resources from books to webinars to in-person trainings.

Human Capital Institute also includes a wide range of podcasts, webinars, and conference opportunities.

Capital Associate Industries (CAI) with HR, Compliance & People Development resources too.

The August organization has a great blog — including this terrific post by Mike Arauz with even more resources for you to explore — and a public Google drive where they share any document they’re able to share publicly.

NOBL, offers a wealth of information related to the future of work, including their A to Z Guide of Culture Decks and an open Slack channel for Org Designers.

CULTURE LABx has articles and hosts events for its global community of founders, designers, and practitioners who experiment with the future of work.

Glassdoor can’t be ignored. Whether you want to take virtual tours of far flung companies; see how people rate an organization, its leader, and its benefits; or read what recent job applicants said about your process, it’s all publicly available on Glassdoor.

Books

There are so many books on this list, Tim! As far as your brain is concerned, audiobooks aren’t “cheating”

Essential Guide to Workplace Investigations: A Step-by-Step Guide to Handling Employee Complaints & Problems Workplace investigations are a fact of People operations. Whether you need to figure out who has been eating someone’s yogurt the office fridge, or investigating a claim of harassment, don’t be caught off guard when the time comes.

The Hard Things About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy Answers by Ben Horowitz is filled with advice that often flies in the face of conventional wisdom. Mr. Horowitz’s book will leave you rethinking the “tried and true” way of doing things, like, “Is it OK to poach a friend’s employee?”

Getting The Right Work Done Time management, both yours and others, is a constant refrain when helping people find their zone. This quick guide from Harvard Business offers tons of tactics to help you win the battle of the urgent versus the important.

Maverick: The Success Story Behind the World’s Most Unusual Workplace by Ricardo Semler was published years before we started hearing Great Place To Work stories from Netflix, Google, Facebook, and the like. Ricardo Semler’s Brazilian-based company Semco was blazing a trail. Change the date from 1988 to 2017 and you can easily forget how many decades ahead of their time they really were.

Barking Up The Wrong Tree: The Surprising Science Behind Why Everything You Know About Success Is (Mostly) Wrong Erik Barker compiles the latest research to remind us that so much of what we think is true really isn’t.

Remote: Office Not Required by Jason Fried and David Hansson of the project management solution Basecamp, breaks down why companies should adopt remote work arrangements, and how they can go about doing it. In this related post, There’s a Channel For That, I detail the various Fractured Atlas communication channels we use for our company with employees working in 10 states.

Radical Focus: Achieving Your Most Important Goals with Objectives and Key Results (OKRs) by Christina Wodtke. Using OKRs can be a powerful tool to help align your organization from top to bottom and back up again. Radical Focus provides a guide for adopting the OKR framework. Not into reading a book? You can watch this video about How Google Sets Goals with OKRs. And if you get stuck during the OKR process and say, “There’s just no way to measure the work I do,” crack open How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in Business.

The Essential HR Handbook: A Quick and Handy Resource for Any Manager or HR Professional is something to keep in your desk drawer for quick reference. You might also prefer The Big Book of HR or Human Resources Kit for Dummies.

The Purpose Economy: How Your Desire for Impact, Personal Growth and Community Is Changing the World by Aaron Hurst looks at how shared purpose culture in organizations can change the world.

Setting the Table: The Transforming Power of Hospitality in Business by Danny Meyer. If your organization comes into contract with people in any way this is an invaluable read.

Gamestorming: A Playbook for Innovators, Rulebreakers, and Changemakers by Dave Gray, Sunni Brown, and James Macanjfo is an terrific resource for those who attend or lead meetings. Not all brainstorming was created equal. Gamestorming is a great tool to help you find the right framework to have the most effective conversation.

Who: The A Method for Hiring by Geoff Smart and Randy Street is one of the best books I’ve ever found on how to structure a strategic hiring process.

The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business by Charles Duhigg. If you don’t understand how habits develop and how to change them, you’re going to be banging your head against the wall forever when working with others. How do you get Bob to start showing up to work on time? Or get a team with a history of delays to finally ship a product on schedule? Filled with fascinating anecdotes, the book will keep you engaged.

Why Work Sucks and How to Fix It: The Results-Only RevolutionCali Ressler and Jody Thompson have written a book that will have you questioning the way you’ve always done things. No mandatory meetings?! Whoa.

Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir examines how scarce resources can make us perform worse than those with abundant resources. Using research that shows even the same people — depending on their level of scarcity — can perform better or worse. The implications for our organizations helps to explain why we more often lose the battle of the urgent versus the important, and adds depth to our understanding of the whole person who walks through the office doors each day.

The Coaching Habit: Say Less, Ask More & Change the Way You Lead Forever by Michael Stanier. Being a people person in the People field isn’t the same thing as being a capital P People person. In the People field, you need to develop skills in yourself and in others to have specific kinds of conversations with people. This book gives you a jump on them.

How Google Works by Eric Schmidt and Jonathan Rosenberg, or check out this slidedeck by the same name. Another glimpse into a company that spends millions trying to determine the best People approaches. Is it a perfect company, no, but don’t let that stop you from learning from them and seeing if you can glean from their experience.

Employment Law quick study guide because ignorance of the law excuses no one. This quick guide will give you the lay of the U.S. Federal employment law land. Be mindful that, depending on where you live in the U.S., the laws can differ. For instance, if you live in California and New York, state employment law includes some alternations that can trip you up.

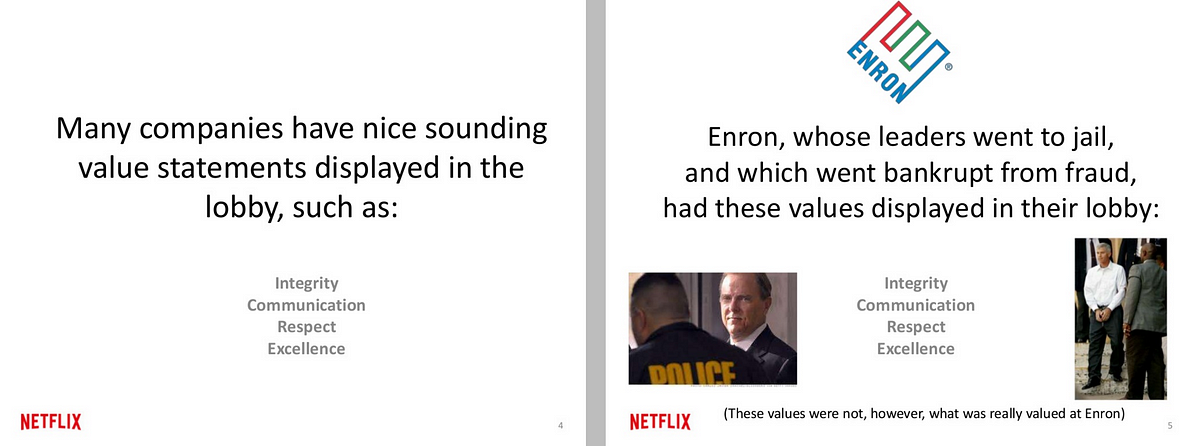

The Advantage: Why Organizational Health Trumps Everything Else in Business by the prolific business parable author Patrick Lencioni might be my favorite work of his. In The Advantage he pulls from many of his previous works —The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Death by Meeting, and Silos, Politics and Turf Wars — to lay out a clear template for how you can determine and articulate your organization’s mission, core values, strategic anchors; as well as create meetings that don’t drain the life out of people.

Teaming: How Organizations Learn Innovate, and Compete in the Knowledge Economy by Amy C. Edmondson provides a great overview of research into how teams can “team” together to learn and improve in uncertain and ambiguous environments.

What Motivates Me: Put Your Passions to Work by Adrian Gostick and Chester Elton provides a framework for helping people identify their motivators. These motivators can be used to personally align them with work, and a la job crafting, help managers and team load balance work with motivators, and then tie specific recognition to each person for their efforts. (Fun fact: With the purchase of this book you get a code to take the What Motivates Me assessment.) Other interesting books by the author duo include All In: How the Best Managers Create a Culture of Belief and Drive Big Results and The Orange Revolution: How One Great Team Can Transform an Entire Organization.

Delivering Happiness: A Path to Profits, Passion, and Purpose by Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh is an excellent story about how a tiny company built itself into people-centric powerhouse. Now they’re taking it to the next level with their foray into holocracy.

Nuts!: Southwest Airlines’ Crazy Recipe for Business and Personal Success by Kevin Freiberg and Jackie Freiberg is another entertaining and rich example of how treating your people well can help you build a successful and profitable company.

Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln by Doris Kearns Goodwin might feel a little out of place here, but it’s a real life case study in how to compile and manage a diverse team towards a shared purpose goal. For more about the quest to build the perfect team, check out this article in The New York Times about Google’s Aristotle Project.

Aziz Ansari’s Modern Romance: An Investigation might feel like another book in the “Which one of these things is not like the others” parade, until you read it thinking about how the research might apply to your recruitment and hiring process. In that light, it might possibly be one of the most entertaining books on the topic.

Thinking Strategically by Avinash Dixit and Barry Nalebuff is a great introduction to game theory, which can feel a little like People operations, depending on the situation. How do you solve the classic “Prisoner’s Dilemma” or de-escalate brinkmanship (as opposed to Brinksmanship, which involves an armored truck).