Scarcity and the Non-Profit People Paradox

By: Tim Cynova // Published: December 21, 2017

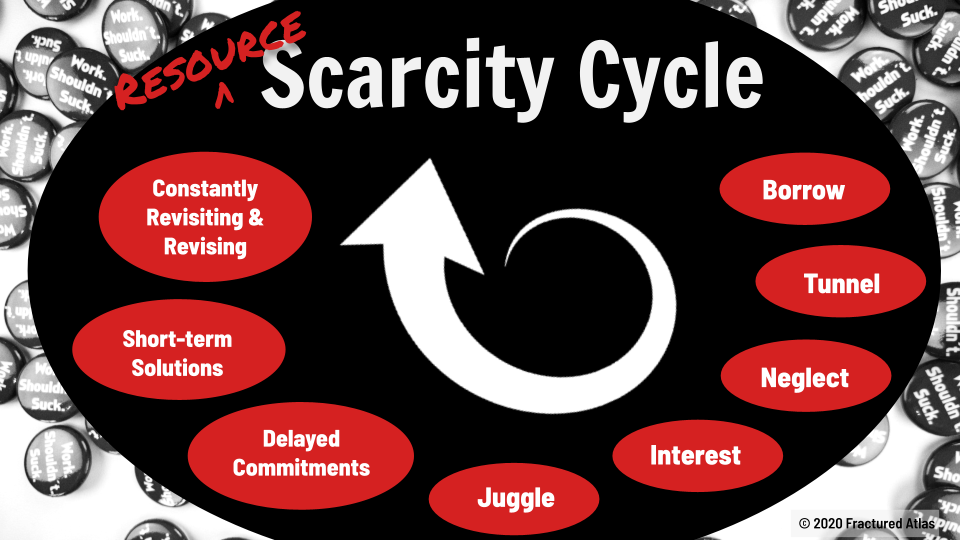

Resource scarcity leads us to borrow, and that pushes us deeper into scarcity. Why? Because when we have scarce resources we tunnel (i.e., we focus on the here and now, the fires, what needs to get done right now). Tunneling leads us to neglect. Tunneling today creates more tunneling tomorrow, and leads us to borrow — in a borrowing from Petra to pay Paula and eventually needing to pay back Petra with significant interest scenario — so that we’re using the same physical resources less effectively, placing us one step behind.

Then, we find ourselves needing to juggle. This creates a patchwork of delayed commitments and short-term solutions that need to be constantly revisited and revised. We don’t have bandwidth to plan a way out of the trap and, when we make a plan, we don’t have the bandwidth needed to resist temptations and persist. The lack of slack and capacity reduces our ability to absorb and weather shocks, and when we do have slack we use it to catch our breath rather than use those moments of abundance to create buffers against future scarcity.

Sound familiar? That’s the scarcity trap as paraphrased from the thought-provoking book Scarcity: Why Having Too Little Means So Much by Sendhil Mullainathan and Eldar Shafir.

How Does The Scarcity Trap Relate to Prioritizing People Ops?

When we tunnel on the urgent — things like making payroll, or getting people to purchase tickets to our events, or reaching our crowdfunding campaign goal, or producing the annual gala to raise funds… to make payroll and present our events — we often do so at the expense of the important, bigger picture, and without regard to the impact on our people and the opportunity costs such focus exacts on our organizations.

Instead, when we focus on prioritizing people, and their capacity relative to our other institutional concerns, we unlock a powerful force and leverage our competitive advantage. So, how much time, money, and slack would you need before you pushed People Ops to the number one thing on your list? And when contemplating that answer, take a moment to consider that our people *are* our organizations.

Prioritizing people — and an organizational culture that allows them to succeed and thrive — creates your competitive advantage.

In not prioritizing People Ops — effectively punting it for another day — you’re borrowing against them and won’t develop the systems to weather scarcity. If we only prioritize people when needing to hire them, we won’t attract and retain the level of talent needed for our organizations to build necessary slack, innovate, and change the world. We’re never going to have the resources to save ourselves. Why?

Most of us believe we’re working smarter not harder. The fact is though, we’re caught in scarcity’s flywheel and it’s cascading a fire fighting, scarcity mindset throughout our organizations, magnifying the problem as things become worse for everyone. We’ll never “catch up.” Worst of all, we’re often oblivious to what will help us out of the bind as we focus on the fires, or assume if we just score that big grant — come onnnnn, lucky major foundation grant! — or sell out our season, we’ll finally be able to get ahead.

Studies show that when our resources are scarce, we’re preoccupied by that scarcity. That preoccupation negatively impacts our intelligence. In side-by-side tests, when we’re distracted by our scarce resources, we perform worse on tests than when answering the same questions when not under resource pressures. (The difference is upwards of a 13-point dip in our IQ!)

Tunneling Tax

Our sector’s common refrain — or badge of honor, depending on how one views it — is that since we’ve been operating with scarce resources for years, we’re skilled at operating under these pressures. Well, maybe. Here’s another research finding: Experience in scarcity makes people better at operating with scarce resources, *but* it also creates tunneling and the related negative consequences. Tunneling responses — increasing work hours, working harder, foregoing vacations — ignore the long-term consequences of these actions.

We introduce quick fixes and patches that come back to haunt us. It’s like purchasing a cheaper washing machine that breaks down more frequently. Putting off a more important task for an urgent one — because we’re tunneling — is like borrowing at high interest. It might address an immediate need but, like that cheaper washing machine, it’s going to come back to haunt us, and require more of us, before we know it.

To deal with the future, we need bandwidth, but scarcity’s bandwidth tax means we can only focus on the here and now. And even when we’re lucky enough to have bandwidth, it can have surprising effects.

And when we get back to the start, we have fewer resources and are farther behind.

When Building Slack Feels Counterintuitive

When you’re already busy, and trying to cram even more stuff into your schedule, the tools to build slack feels counterintuitive. Rather than trying to cram everything into a packed schedule — I just need more time! — building in slack increases our ability to get things done. (Don’t believe me? Read the illuminating Example 2 below.)

What does this mean for us in the cultural sector? Sometimes there’s a way to solve a perennial challenge that runs counter to conventional wisdom. Sometimes it’s not about needing more money or more people.

Thought experiment: At a recent conference, I heard a speaker say, “In our overworked, under-resourced organizations, how are we supposed to make progress?” Well, what would it look like if our “overworked” and “under-resourced” organizations had exactly the same resources but weren’t overworked, delivered on their missions, and changed the world?

What would it look like if your Development Associate wasn’t slammed wall-to-wall with more work than could be accomplished during an eight-hour day. What if they had flexibility in their schedule? How could that slack help your Director of Development and development department be better able to execute their work (and when I say “work,” I’m also including time to think, dream, and experiment).

When you manage bandwidth and not hours, you start to see other benefits. Henry Ford is credited with popularizing the standard five-day, 40-hour work week. It wasn’t that he was benevolent. It was that he recognized it made workers more productive during their “on” hours because they were healthier, more focused, and made fewer mistakes.

What Can I Do About This?

First, focus on your people: what you are asking of them, the environment in which you’re asking them to do it, and the type of support and feedback they receive. Focus on building diverse teams that level up and break through in ways that homogeneous teams can’t. If everyone has the same relative background and experience, even if you have a moment to consider how to deploy resources if you didn’t do an annual gala, you’re less likely to end up with innovative alternatives.

Second, you can’t do everything and need to make tough choices about what can be accomplished. Again, what would it look like if overworked and under-resourced organizations had exactly the same resources but weren’t overworked and didn’t feel under-resourced? It likely would mean they’d have to make tough, probably painful, choices to consciously *not* do things they love. It’s like pruning your prized plant so it can grow and be healthier.

If you say, “We don’t have the resources to accomplish everything we need to do,” than you’re trying to do too much. You might reeeeaaaaaally love that thing, but if it’s undermining your ability to deliver on your mission without burning the place to the ground, you need to take it off the list. You need to stop doing it. Quality over quantity here. (See also: Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.)

Lastly, once you’ve pruned and protected, get ready to lean in when you have periods of slack and abundance. It’s counterintuitive, I know. “I just need a break and a breather” is often the natural inclination. Kicking yourself into a higher gear when you have periods of abundance — and determining ways to smooth out the ebbs and flows — will enable you to bank slack for the future.

Can You Help Me Out Here?

Want to level up your People Ops to create more periods of slack and resilience? Here’s an extensive list of People Ops resources covering a whole host of topics. Want to chat about this or another People Ops challenge that’s on your mind? Connect for free HR assistance and ping me at hrhour@fracturedatlas.org.

Special thanks to my coworker Lauren Ruffin who introduced me to the resource scarcity research through this article that set me on this path of discovery, a journey that further solidifies my resolve that strategic People Ops are key to helping us address the challenges we face in the cultural sector.

Extra Credit: Illuminating Real Life Examples

Example 1: Chennai, India

One research study cited in Scarcity followed street vendors in Chennai, India. These vendors earn $1/day and take loans to buy their goods that charge interest rates of 5% daily.

The study divided people into two groups. The first group operated as usual: in debt, earning $1/day, and borrowing money at 5% daily interest to pay for their goods to sell. The second group was given a one-time infusion of cash to pay off their debts and break free from the trap. The researchers then tracked the two groups for a year. What happened?

Within a year, all the vendors were back in the same place, in debt, living on $1/day, and needing to take loans with 5% daily interest. Why? While they momentarily had bandwidth and slack, they didn’t have enough slack to weather the hits that would come along the way: buying school clothes and supplies for their children; unexpected medical bills for themselves and their family; and so on.

The Indian street merchant study offers a powerful, and sobering, example to those of us in organizations who “just need that one grant to finally have room to breathe.” “If we can just secure the $100,000 grant, we’ll be able to get ahead of the curve.” Even if we get it, we’ll likely find ourselves right back where we started.

Example 2: St. John’s Regional Health Center

When we’re tightly packed, we reduce slack. St. John’s Regional Health Center performed upwards of 30,000 surgical procedures a year in 32 operating rooms that were always fully booked. Staff were performing surgeries at 2AM, waiting hours for an open room, working unplanned overtime. “The hospital was like the over-committed person who finds that tasks take too long, in part because the person is over-committed and can’t imagine taking on the additional — and time-consuming — task of stepping back and reorganizing.”

The hospital would start the week with its operating room schedule. Before they could even get going, emergency surgeries would crop up that would bump elective surgeries, and then those elective surgeries would bump other elective surgeries later into the week until more emergency surgeries bumped those, and pretty soon people were operating late into the night and on the weekends. Knowing surgeries would likely be bumped, surgical teams would schedule all of the elective surgeries early in the week, which caused further bumping when the surgeries actually were bumped… which caused more bumping. This led to the teams being more exhausted, unhappy, and a general feeling that, “if we only had more operating rooms we could get this back on schedule.” (Sound familiar to resource constraints in your organization? If we only had x, y, z.) So, what did the hospital end up trying?

They realized that while a percentage of the surgeries were emergencies and were unplanned, they weren’t *unexpected.* The same thing happened every week. Here’s where a bold, counterintuitive approach came into play. The hospital took one of its operating rooms offline and allowed it to be used *only* for those unplanned, but not unexpected, surgeries. Everything else needed to be scheduled in the other operating rooms. As you can imagine, this move went over splendidly. Well no, people were furious, “How could you take away an already precious resource!?!?! We don’t need fewer rooms, we need more!!”

What they found was that with one operating room set aside for unplanned surgeries, the other surgeries weren’t being bumped as frequently. This in turn allowed teams to more confidently schedule elective surgeries for later in the week without fear that they’d roll into the late night or weekend. This evened out the schedule, reduced the long work hours and weekend surgeries, resulting in more focused teams that made fewer mistakes, and people feeling less stressed and unhappy. Voilà!

Example 3: New Jersey Transit

Those who ride the rails on a regular basis are well aware of this classic example. If there’s little to no slack in a system, then any train delay forces all the trains behind that one to be late as well. It’s impossible to “catch up” by leaving the station early. You can lose time, but never gain it back. Minor delays therefore pile up and quickly turn into major delays on a regular basis. (Example provided by my friend whose commute on NJ Transit provides him with daily reminders of why slack in systems is so important.)

Example 4: Slack vs. Fat

Corporate cost-cutting in the latter part of the 20th century famously resulted in “right sizing” and cutting “fat” out of companies. “Oh, you have an assistant who has work to fill about a third of the day? Well, now you share that assistant with two other people.” On the face this appears to make sense. Counterintuitively though, this created unintended cascading scarcity trap issues. Now the assistant had a full day’s worth of work but lacked bandwidth to help when something urgent arose. This meant that the urgent bumped the important with cascading effects to the three people they worked with and beyond.

Congratulations! You’ve completed the extra credit portion of this piece.

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.