THE BLOG

Assessing a Four Person Non-Hierarchical Leadership Team

The Fractured Atlas leadership team in 2019: Tim Cynova, Lauren Ruffin, Shawn Anderson, Pallavi Sharma

By: Tim Cynova // Published: October 9, 2019

Challenge

How does a Board of Directors (re)craft its annual assessment of the CEO when that role is filled by a four-person, shared, non-hierarchical leadership team? This was precisely the challenge the Fractured Atlas Board faced in early 2019. Below, in detail, we describe the process we crafted to answer this question.

Quick recap

Fractured Atlas has officially been operating with a shared, non-hierarchical leadership team since January 2018. Functionally, we’ve been doing it for about a year longer than that. In advance of Fractured Atlas founder Adam Huttler leaving the organization to become CEO of Exponential Creativity Ventures, staff and board leadership engaged in lengthy conversations about what succession plans might look like. Ultimately, we decided that instead of replacing the CEO “one-for-one,” we would explore a four-person, shared, non-hierarchical leadership team structure. There were multiple reasons why we landed on this model. Here’s more about that decision and how the whole thing works.

The Annual Assessment

One of the core responsibilities for a Board of Directors is to assess the performance of its chief executive. Performance appraisal is an area of HR that even those who do it daily find more art than science. Introduce a volunteer board, who might not possess this specific expertise, further complicate things in that they only engage episodically with its CEO, and you potentially have all the ingredients for potential disaster. Now call it non-hierarchical *shared* leadership among four staff members, and things get quite a bit more complicated. (And to make things more complicated for ourselves at Fractured Atlas, we specifically designed this team structure in a way to avoid a “first among equals” power imbalance.)

With all of this complexity and potential pitfalls at play, it’s one of the reasons why we love our Fractured Atlas board. They, like the staff, relish opportunities to venture into uncharted waters and wrestle with difficult, unusual scenarios. They bring a great deal of wisdom, and perspective, and humility to the table that enables staff and board leadership to truly work in partnership. Because of this, the staff leadership team doesn’t constantly feel like we need to “manage” the board. We’re not spinning information in just the right way to keep the board engaged but, you know, not *too* engaged. It was with this relationship that we set out to design a new shared leadership team assessment.

While we have effectively been operating as a shared leadership team for more than two years now, the *official* one-year anniversary rolled around earlier this year. And with it, the need to assess how well this atypical leadership arrangement was working for us. This prompt lead to multiple conversations between staff and board leadership, and caused us to question the basic premise and purpose of a performance evaluation: how might we can construct one that best suits our needs? What does an assessment for this kind of CEO arrangement look like? Even more fundamental, what’s the purpose and value of a leadership assessment? What’s the value of an annual assessment to the individual staff members? To this team? To the board, other staff, and the organization? How does this track to us fulfilling (or not fulfilling) our organization’s mission and purpose?

We surfaced several key criteria from these discussions:

We wanted to collect voices from around the organization.

We wanted to assess the four people collectively as the CEO function.

We wanted to lay the groundwork for future assessments.

Each of the four individuals on the leadership team oversee an aspect of Fractured Atlas, and they operate as the CEO of sorts for their department (i.e., Programs, Engineering, External Relations, and FinPOps (Finance, People, Operations)). We wanted this assessment structured in a way to evaluate the group as a whole. How well is this group functioning as the CEO of Fractured Atlas? Not the individuals. The leadership team makes decisions of consequence as one entity. It’s not Shawn making this big decision and Lauren making that one. We didn’t want the assessment to be about how well is Tim doing in his job, or Lauren, or Pallavi or Shawn, and then we roll it all up into a team. We wanted it to evaluate the “CEO” as this leadership team configuration. We know from research and experience, that a team can all be comprised of individual “B-level players” but function as an “A-level team.” That’s what should matter to the organization. Similarly there are plenty of examples in life where a collection of A-level players barely manage to function as a C-level team. [Insert your highly-compensated heartbreaking hometown sports team here.]

We settled on a three-pronged approach:

(Part 1) A modified 360-degree review collecting information from board members and from staff who had direct knowledge from working with the leadership team. Ultimately, six staff members and all of our board members were interviewed for roughly 60-minutes each over Zoom video. (For this part, we partnered with the terrific Kelly Kienzle of Open Circle Coaching.)

(Part 2) A way for the leadership team to assess its own team performance. (For this part, we used Patrick Lencioni’s Team Assessment framework.)

(Part 3) A way to capture an explicit professional development component for each of us. For example, in evaluating the four-person team as a single entity, we were omitting individual feedback that would be useful to each person’s professional growth. (For this part, we engaged in a confidential meeting for only the four team members. More on the structure below.)

Part 1: The Modified 360

For the initial assessment of the shared team, we felt it was important for people to weigh in who had direct knowledge of the group and their activities. We wanted people who worked with the team, saw the interactions firsthand, engaged with them in challenging conversations, and who knew the members for longer than just a few months. (In future years, we aspire to simply pull names out of a hat to pick people.)

The objective of conducting these team input interviews was to receive input from colleagues regarding the leadership team model’s areas of strengths, as well as how the model could be improved. Kelly conducted live, confidential interviews to gather suggestions for improvement that would enhance both individual performance and the performance of the team overall. Interviewee input was used to help assess both the effectiveness of this leadership model as well as the leadership team itself.

Her guidance to interviewees included:

Interviews of 60 minutes will be conducted with team members, direct and non-direct reports, and board members. Interviews will be conducted via Zoom video.

All information collected during these interviews will be held confidentially. No direct quotes will be taken and no names will be attributed to any comments.

A minimum of 3 interviewees expressing the same sentiment on a given issue is required to ensure confidentiality and to identify common themes in the feedback.

These common themes will be collected into a Summary Report that will be shared directly with the leadership team, the Board Chair (Russell Willis Taylor) and possibly other Board members.

In advance of the interviews, Kelly worked with the staff and board leadership to craft the following prompts that would be used to guide her conversations:

What are three words you would use to describe the effectiveness of this leadership model?

For what would you hesitate to rely on the leadership team?

What are the greatest collective strengths of the leadership team (not of the individuals)?

What would you prioritize as the leadership team’s greatest opportunities for development?

How could the leadership team foster a better working relationship with you personally or the organization as a whole?

To establish a baseline for the performance of this model: “How effective is this 4-person model in leading the organization as compared to the single CEO model when Adam Huttler was leading Fractured Atlas?”

Following these interviews, Kelly processed the information and compiled it into a 31-page document. That document was delivered to the full board, and discussed during a 90-minute Zoom meeting with the leadership team, Kelly, and board chair.

Part 2: The Team Assessment

The first part of the process collected external perceptions on the leadership team. We now needed a way for the four members of the team to assess our group performance. For this we turned to Patrick Lencioni and his infamous business fable The Five Dysfunctions of a Team.

Lencioni has developed a 38-question assessment that team members complete to rate the group on his five dimensions: Trust, Conflict, Commitment, Accountability, Results. Each question is rated on a 1-to-5 scale of Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Usually, Always. You tally the individual scores at the end and, voila, there’s a numerical value for each component that maps to how well the team feels its doing. The idea is that teams take this on a regular basis (quarterly, semi-annually, etc.) to track how each component is tracking over time. (We complete this assessment on a semi-annual basis.)

Following this assessment, the leadership team met to discuss our reactions. What were the questions and components where we were all in agreement? What questions and components saw the most variety in answers? Why might that be? How might we approach our work in ways that address some of the more challenging aspects we need to improve in our working relationship?

Part 3: Individual Effectiveness

We felt like the first two parts of the assessments gave us great information about how we were working together as a team. However, we were missing a piece of *individual* feedback that typically occurs during one’s annual assessment: (1) here’s where you’re awesome, and (2) here’s where you can be even awesomer. Because of how we structured this overall assessment to focus on the team entity, we were missing an individual professional development aspect. For this component we again turned to Patrick Lencioni.

Each of the four of us answered the two questions below for each of the other three team members. And while we could have reflected on how we’d answers these questions for ourselves, we didn’t include that this time around.

What is [Lauren/Pallavi/Shawn/Tim’s] single most important behavioral quality that contributes to the strength of the team? (That is, their strength.)

What is [Lauren/Pallavi/Shawn/Tim’s] single most important behavioral quality that detracts from the strength of the team? (That is, their weakness or problematic behavior.)

This part of the process was entirely confidential to just the four members of the leadership team. We’ve cultivated a great deal of trust and understanding between us that enables our team to delve into challenging topics. We felt like if someone else joined this meeting (also done entirely on Zoom video), or if the information was shared outside of that circle, we’d potentially “pulling punches” rather than being open and honest, particularly when it came to the things we each needed to work on improving.

Assessment Themes

In Kelly’s 31-page document she highlighted a number of themes from her conversations. Each of the seventeen items below had a page of supporting comments. Some of these findings support our earlier understanding of shared leadership models from research; some we came to discover once we were actually doing the thing; and still others were new themes to contemplate and explore in the coming year.

The model represents and encourages diversity

The model reflects our values and mission

The model is effective and efficient

The model enables us to be bold

The model generates collaboration

Responsibility is shared and that’s good

Responsibility is shared and that’s difficult — Staff’s concerns

Responsibility is shared and that’s difficult — Board’s concerns

Seeking an answer from 4 people is frustrating and slow (but maybe the quality of the answer is better)

Create more transparency in decision-making

Make it easier to approach leaders

This model is exhausting for the leaders

This model is better than single CEO model

This model is potentially better if we address vulnerabilities

Re-imagine how Leadership and Board work together

Establish how the Board will evaluate the leadership

Need to understand why/how these individuals are so successful together

After she delivered her report, the Leadership Team met via Zoom video with both Kelly and Russell Willis Taylor. We discussed the themes and comments, sought clarification in a few areas, and then chatted about what future work to support this topic might look like.

Reflections from an Outside, Independent Party

At the end of her report, Kelly collated a list of recommendations (expressed by the interviewees) on what has made this model effective. She suggested that they might be of interest to other organizations considering a shared leadership model. A number of these align solidly with our previous research into the “how” of creating high-performing shared leadership configurations.

The leadership team must have:

Trust [Kelly’s Note: Understanding how this trust was created on this team is a key question that this entire process sought to answer. This model’s success appears to be fundamentally tied to the trust that exists between these four leaders and/or their individual capacities for trust. The question is whether that trust is a necessary prerequisite or invaluable end-product of using this model. Most likely, it is a fortunate combination of both.]

Collegiality and mutual respect

Comfort with complexity

A leadership assessment of each participant for key leadership qualities

An organization-over-individual ethos

Deep self-awareness

An understanding and acceptance of the flaws of one another

A representation of the organization’s values in the leadership model, while still maintaining equitable recruitment practices

A representation of strong expertise in each relevant content area of an organization

A representation of the fundamental skills of leadership: idea generation, aligning people and execution

Complete buy-in from all participants impacted by the model

A stronger board leadership, and especially Board Chair, than is otherwise required

A norm of non-crisis scenarios, as effective crisis response would be more difficult under this model.

Where to from here

The 2019 assessment process officially closed with a letter from the Board Chair to the Leadership Team. It memorialized this moment, went into the personnel file, and then we moved on. From the annual assessment, and our continued staff/board work, we identified two items specifically mentioned in the assessment to include in future conversations:

How might the Board assist the Leadership Team with the ongoing capacity challenges that they face as leaders of a very lean organization?

How must the Board’s role change in light of the new leadership arrangements to make sure that it contributes real value to Fractured Atlas?

Time will tell how we modify the 2020 assessment process. As with everything at Fractured Atlas, we’re continually iterating and adjusting to best align what we do with what we need. Stay tuned for that recap piece next year.

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

Working From (Almost) Anywhere: Virtual Realities and a Fully Distributed Workplace

Long exposure image I captured after a productive day of writing in this former one-room school house.

By: Tim Cynova // Published: October 2, 2019

Fractured Atlas “Fun” Fact

Of the eight staff members currently at the Senior Director and C-level tiers, none live and work in the same state (Colorado, Indiana, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Vermont). And more than half of our Fractured Atlas team now live in 11 U.S. states and 6 countries, with fewer than half spending any time in our sole physical office on 35th Street in New York City.

Why do I mention this here? Because this is all part of our effort to create a thriving workplace — that’s entirely virtual (or distributed) — without any physical office by January 1, 2020. [Note: Our Programs and External Relations teams will be communicating more specifics about how this transition will change some of our processes. Stay tuned.]

We’ve been planning and moving towards this transition for quite some time. Our intrepid board of directors is already there with members living in four countries. Quarterly board meetings take place by Zoom video and see people joining from at least six times zones (with two people usually joining meetings from tomorrow). For our recent meeting, we had members joining at 2AM, 6AM, 8AM, 1PM, 3PM, 5:30PM, and 10PM. (That’s true commitment to an organization when you join a video call at 2AM.)

Fractured Atlas office circa 2009

Vintage Office

The decision to transition to an entirely distributed organization didn’t come out of the blue. Like many organizations, we once had one physical office where every single staff member worked five days a week. We each had our own assigned desk with desktop computer, phone with a cord that plugged into the wall, and a few photos of friends and family. When we had meetings, everyone who needed to attend got up from their desk and walked into our tiny conference room.

Iterate & Adjust

Eventually, we started experimenting with how to structure our work and workplace. “How about one Director-level staff member tries a set work from home day once a week for a few months?” Then we evaluated it. What worked, what didn’t. Iterate and adjust. Then we experimented with two people. Then that became a standard option for Directors (a position that affords more agency in the type of work they do). Then we introduced a computer-based VoIP phone application allowing people to untether from a dedicated desk to take phone calls.

This lead to us experimenting with a work from home (WFH) day for three months with a staff member at the Associate-level (someone who primarily provides customer support for members on phone and through a web-based helpdesk application). Then, we hired our first non-NYC-based employee. Then we increased the number of Associates working from home. Then we acquired and integrated a software development company where no two engineers lived in the same state. Then we switched from desktop computers to laptops, and bought an Ikea couch and comfortable armchairs for the office. Then we hired more non-NYC-based people. This evolved over several years to bring us to where we are today. Until recently, our official WFH policy simply stated “after working with Fractured Atlas for at least a year you can then request a set WFH day.”

Why Do We Do It *That* Way?

The journey towards becoming an entirely distributed organization started several years ago when we ran out of room and chose to renovate our office. During the run up to that renovation, we asked ourselves questions about how we used a physical space, and how that space could be designed to best support the different types of work we needed to accomplish throughout the day.

We asked things like: Why do we use a conference room? What kind of work does that type of space support? What if we didn’t have that space, how would we accomplish those things instead? What kind of environment best supports grant writing? Or talking on the phone assisting our members? How does energy and focus change throughout the day? And what conditions would increase the time we each spent in “flow”?

What does working at Fractured Atlas look and feel like in five years?

We stumbled upon a seemingly simple question that now contributes to our workplace iterating at Fractured Atlas: What do we want working here to look and feel like in five years? Contemplating this question helped us realize the leap we needed to make from maintaining a physical office to being a fully distributed organization. In its simplest form, in five years, working at Fractured Atlas doesn’t look like everyone working in the same physical office circa 2009, and certainty not one in Midtown Manhattan. If anything, the trend over the years for us has been for staff to relocate *away* from NYC rather than towards it.

As we thought about how this workplace vision intersected with our commitments to being an anti-racist and anti-oppressive organization, the transition made even more sense. It affords people rare agency to make decisions about how they want to craft their life in ways that weren’t previously possible. “You live [here] because your job is [here],” no longer would apply.

Specific City Not Required

This vision enables us to hire and retain amazingly talented people who don’t live in the same location. New York City is an expensive place to live. At Fractured Atlas, we anchor our strict fixed tier comp and benefits off of the NYC marketplace, regardless of where people choose to live (i.e., every person at a given tier is paid exactly the same regardless of how long they’ve been in that role at Fractured Atlas and irrespective of whether they live in NYC, Philadelphia, or Dallas). People are welcome to live in NYC, but they can now relocate to, say, Cincinnati, OH and potentially greatly increase their standard of living and purchasing power.

Juggling Multiple Organizational Cultures

Transitioning to entirely distributed would also eliminate a significant silo in our organization: those who work fully virtual versus those who work in HQ. It would go a long way toward “equalizing” that experience in a way that isn’t possible when a significant portion of people work together in a physical office.

How might we work to equalize the experience of working at Fractured Atlas, so everyone feels like they work for the same company rather than different experiences depending on their relationship with a physical office space?

There’s a wealth of research about how virtual work impacts employees. One particularly illuminating piece I read early on in my own journey was “Knowing Where You Stand: Physical Isolation, Perceived Respect, and Organizational Identification Among Virtual Employees.” It was co-written by friend and former Fractured Atlas board member Amy Wrzesniewski, and based on research she and her colleagues conducted. (A selection of other resources, some more anecdotally based and less scientific, are linked at the close of this piece.)

As more Fractured Atlas staff members were working virtually, we wrestled with the question about whether it was possible to “equalize” the experience for those who work fully virtual and those who work solely from HQ. Was it possible to make it feel like everyone worked for the same Fractured Atlas? Especially for those who were hired and then — even though they work closely on a daily basis — might wait upwards of a year before they meet the other members of their distributed team in 3D for the first time.

The more we dove into preparations to transition to a fully distributed organization, the more we realized that we were not trying to maintain only two different organizational cultures — one for those onsite and another for those offsite — we had created, and were trying to manage, at least five different location-related organizational cultures. We had:

(1) Those who worked entirely remote,

(2) Those who worked 5 days a week from the Fractured Atlas office,

(3) Teams where no two members lived or worked in the same location,

(4) Teams where part of the team was remote and part of the team worked from the Fractured Atlas office, and

(5) At least one team where — when factoring in flexible work from anywhere days, travel, vacations and sick days — they seldom had two days with the same HQ/virtual configuration.

That last item in particular exacerbated the stress, uncertainty, and anxiety of a distributed team, because you simply never knew exactly what the configuration would look like from one day to the next. And this feeling permeated at the individual, team, and organizational levels. Moving to an entirely distributed model would at least, in some ways, alleviate this stressor.

Some Staff Are Already There

It’s easy in a change initiative — particularly for those of us who are “losing” an office and our daily routines on 35th Street — to forget that we currently have an organization where more than half of our colleagues already work virtually. More than half of our coworkers have figured out how to do this well and, for them, a transition to being entirely distributed is only likely to improve their work experience.

How might their experience of working for and with Fractured Atlas change for the better? And what can we learn from our colleagues about how they’ve configured home offices and routines to thrive? What can we learn from our coworkers about how to schedule the day? Do people wear shoes when working from home? How do people replicate the positive benefits of those serendipitous in-office chats when it’s just them and maybe their pet? And, most importantly, how do you remember to eat lunch? [Our How We Work, Virtually blog series shares some of those stories.]

With So Much to Do, Why Prioritize This?

At any given time, the Fractured Atlas teams are juggling 3–5 significant, high-priority projects. Most of these focus on developing our products and services to better serve our membership. In some cases though, we focus more internally on how we approach — and can better accomplish — our work and mission.

There are several reasons why our move to be an entirely distributed organization rose to the surface:

Changing Work Patterns. Through our regular operations, we almost by accident ended up with more than half of our team working outside of the New York office. And everyone at Fractured Atlas now works virtually at least one day a week. This leaves an office designed to support 30 people routinely with about 5 occupants on any given day.

Finite Resources & Opportunity Costs. The ten-year lease we signed with terrific terms at the bottom of the real estate market in 2009 is quickly coming up for renewal. With finite resources and associated opportunities costs, every dollar and our related energy spent on maintaining a physical space for fewer and fewer people means we can’t use those resources elsewhere. Even moving to a smaller office still consumes a huge amount of capital and time that could be otherwise dedicated to delivering even better products and services to members, and a better working environment for staff.

Standard of Living & Larger Applicant Pool. In not having to work and live in NYC, Fractured Atlas has access to a huge pool of terrifically talented people who otherwise might not want to live and work in NYC. For those who love their work at Fractured Atlas but no longer want to be in NYC, it means they have the agency to choose where they want to live first. And for those who love NYC? It means many are now gaining upwards of 3 hours a day in discretionary time that previously was spent commuting.

Into the Future! When we reflected on the future of our organization, the culture we wanted to maintain, and how we wanted to create a place where people thrived, having a physical office didn’t rank high on our list of priorities or as a motivator to achieving our goals.

Think of All the Money We Won’t Save

When I mention our move to being an entirely distributed organization, many people respond by saying, “Wow, what a savings! It must be great to get rid of your rent and utilities expense!” In reality, the expense factor was almost an afterthought. (Don’t get me wrong, it was a thought, but not the one that directed us down this path.) While we will likely see some financial savings as a result of this transition, it’s not likely to be as significant as most people assume.

In exchange for rent and utilities, we’ve already incurred higher application subscription fee costs (e.g., Zoom, Dialpad, Slack, Trello). And we’ll incur increased travel and occasional coworking facility costs to address the effects that being physically isolated from coworkers introduces. Our Internet costs will also increase since we’re requiring that staff have high speed Internet connections as a work condition, and thus will be reimbursed for that monthly expense. (There are only so many video and audio calls you can do with spotty service before your coworkers and customers lose patience.)

You’ll likely be disappointed if money is the primary motivator to make this change. With any change initiative, the stronger and more substantive the underlying purpose for the change, the more ballast you have to steady the ship when it’s being tossed about on the sea of change. Why are we doing this thing? To save money — [cue sad trombone sound] — won’t inspire much. While wise resource allocation is important, it’s not usually a solid enough reason to get people to jump out of bed in the morning. Again, it’s not that it doesn’t have merit, but I bet you can drill down to a more purpose-driven answer than “save money.” For us, it’s about continuing to craft a workplace where people can thrive, and one that enables us to better serve our members. And *that’s* why we went about making the change.

Younger me, skeptical of Work From Anywhere arrangements.

I Haven’t Always Been a Fan

Over my decade at Fractured Atlas, I’ve seen us grow from a handful of people to nearly 40. I was part of the group that moved us, box by box, into our current office space that afforded us, at the time, *way* more space than we needed. I was there when we renovated it because we had too few places to work in an always-packed office. And I’m here now, almost as it was in 2009, with just a handful of people in a way too empty space. It’s beautiful and convenient and has colleagues in 3D that I thoroughly enjoy working with.

But lest you think I’ve always been a Work From Anywhere (WFA) evangelist, for many years I feared that in us being more virtual we’d lose the soul of what it meant to be Fractured Atlas. We’d drain the culture that made us, well, us.

Worried that more people working remote will change the company culture? For us, it did. It also allowed us to hire incredible people we otherwise wouldn’t have been able to work with. It introduced flexibility with how and when people do work so that they had more agency in their life. And, maybe most importantly, it has allowed us to serve our members in more and different ways.

What I realized a few years back was, just as I’m no less me than I was 25 years ago, I’m me, but different. Same with you. If we look at humans on a cellular level, over 25 years, most of the cells in our bodies have been replaced. But somehow, we’re still us. Organizations are similar. When I was afraid of us losing our organizational culture, I didn’t consider the culture we were building as a direct result of our organizational culture. The thing we were building was the thing we were building because of the thing we built. (Yep, I know, slightly convoluted, but thanks for staying with me there.) The DNA-level stuff about Fractured Atlas was still there, but now with increased resiliency and flexibility and adaptability as we cultivated a place where we didn’t all physically work in the same space.

Experiment, iterate, and be purposeful about the kinds of things you can do in a space. Also, don’t forget to be a human.

Crafting Your Own Experiment

Like much of what each one of us does in life, someone has figured out how to solve it, somewhere. It’s the proverbial “solved problem.” Part of our iterative and creative process at Fractured Atlas leverages those learnings. (It’s why we’re constantly reading, listening, and looking across sectors for case studies, different perspectives, and solutions.) And then we, in turn, feel a responsibility to give back by sharing what works and doesn’t work in our own approaches. There are 7 *billion* of us on this Earth learning and doing. Let’s not recreate the wheel if it’s not necessary.

When it comes to alternative work arrangements, you certainly don’t need to give up your office entirely to ask: What do we want work to look and feel like here in five years? With those answers in mind though, begin to experiment. Here’s what’s comforting to me about this: plenty of people have come before us and have figured out ways to address even the most complicated of these issues. We get to leverage those learnings to create an environment that fits us and our organization best and how we want to work.

If you’re not sure where to start, here’s a quick list of some helpful places to get you going:

Tools to Try

Even if you’re not convinced that people should work outside of your office, you can start to experiment and iterate with tools to improve workplace communication, transparency, and productivity.

Introducing communication tools like Slack or Flowdock will eliminate countless email threads when all you need to do is have a quick chat between a few people. Use a Zoom video for meeting the next time you’re trying to coordinate a meeting with someone offsite. (Think that “quick chat over a cup of coffee.”) Learning how to facilitate and participate in a video conference call is a professional skill people need to develop, just like the proper format for a business letter.

Try using a whiteboarding tool likely Mural to replace everyone standing by a physical board. Being intentional about using a tool like Mural has the added benefit of keeping you focused on the task at hand and often eliminates side conversations that take you off track or burn valuable time. Track projects and priorities in tools like Trello. (Pro tip: We use it to compile and manage meeting agendas, and then track our action items.)

Then there are frameworks like OKRs to create transparency, alignment, and accountability around the work that everyone is doing. Objectives and Key Results (or OKRs) are a huge asset when incorporating work from anywhere arrangements. They help build the trust necessary for high performing teams. Now I don’t need to physically see you “working” in an office to know that you’re making progress on our previously discussed and approved projects. Whatever you choose, just start experimenting and iterating.

Where Does This Leave Us

What will it look and feel like to work at Fractured Atlas in five years? I’m not entirely sure. I’d be lying if I said that I had a clear idea. What I do know is that we have a sense for what it might look like and are making directionally-correct iterations towards that goal. In the end, the important part here is making sure that what we do today sets up Fractured Atlas of the future with the things it will need to be successful in service to our mission then.

On a practical front, we continue to work through Project Blue Whale (as our coworker Nicola has dubbed this in the plan outlining each stage of this transition). Each day brings new, fun questions to wrestle with. How and where do we receive mail? How do we deposit checks, and cut checks? What’s our corporate address for tax forms when we don’t have an office? How do we get three “wet” signatures on this form when everyone lives in a different country? How often and where do we meet coworkers in 3D? Where do we store spare equipment like laptops?

However we end up answering these questions, it will be done intentionally as we work towards a future of Fractured Atlas that best supports our coworkers, mission, and members.

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

Bring Your Whole(ish) Self to Work

By: Tim Cynova // Published: March 29, 2019

Remember when it seemed like everyone was trying to achieve “work-life” balance? More recently, perhaps in a nod to the challenges of balancing “work” and “life” in an always-connected world, or maybe because for those searching for meaning and purpose in their activities there’s not always a bright line distinction between “work” and “life,” the phrase has shifted to “bringing our whole selves to work.”

Well, with my HR hat on, it’s typically people who bring their whole selves to work who are the ones the HR folks need to have meetings with, or about. So, I’d like to propose a slight reframing: let’s aim to bring our whole(ish) selves to work. 85% of ourselves is probably just about the right calibration.

Why 85%?

In the end, not even our closest friends and family *really* want us to bring 100% of ourselves to our interactions. Yes, be present, genuine, and authentic. But no to bringing every single piece of us into the space. When we do bring 100% of ourselves into a space, how might that actually make it more challenging for others to show up more fully themselves?

Not scientific.

I’ll bet most people don’t exceed the 50% mark though. For many, it’s less about how to dial back from 100% and more about what conditions would be necessary to bring a little (or a lot) more of themselves.

Looking at this through the lens of building high-performing teams — where people can thrive — we can see even clearer why aiming for everyone to move towards 85% might be the better pursuit.

Psychological Safety & Diversity in Teams

Research shows that two traits of high-performing teams are psychological safety — the ability for people to participate without fear of retribution (the ol’ getting your legs kicked out from under you when you say something the boss doesn’t agree with) — and that teams are diverse in as many ways as possible. Both of these play significantly into people feeling comfortable bringing more of themselves to work.

Here’s just a sampling of the ways diversity can show up in our organizations: sex, gender, age, race, religion, national origin, ethnicity, disability, sexuality, income, learning modalities, education, culture, customs, life or prior work experiences, networks, style, speech, lineage, origins, political beliefs, appearance, and work styles (just to name a few).

Thinking about where people calibrate themselves with regards to that 85%, I imagine in U.S. corporate culture, aside for a number of heterosexual, White, cis-gender men in positions of power (or perceived power), many others feel a struggle of varying levels to bring their wholes selves to work, and/or are conflicted about what and how much they want to bring of themselves. This creates a drag on people’s ability to be authentic, do their best work, and thrive. And the sad fact here is that while we’re talking about bringing our whole selves to work, some of our colleagues are likely comfortable bringing only about 20% of themselves to their work.

How much richer and more meaningful would our organizations be if everyone felt comfortable bringing 85% of themselves to work?

How much more meaningful and engaged might someone be if they felt they could go from bringing 20% of themselves to, say, 60%? How might this result in more of us being able to fulfill our organizational missions and our personal search for purpose?

As we work to build more inclusive, diverse, and/or equitable teams and organizations, it’s incumbent upon those of us in positions of leadership — wherever we lead from in our organizations — to do whatever we can to assist in creating an environment that’s supportive of everyone bringing more of themselves to their work (and pointing out for those few people who might need to dial it back, when that’s appropriate too).

Why is this important?

First, because it’s the morally right thing to do. If leaders aren’t continually trying to make progress in supporting those who work for their organizations, they are failing at a core leadership responsibility. However, if we can’t agree there, let’s move more to the business case.

I’ve written about how research shows the vast majority of people who work at our organizations are disengaged from their work, and that more than half are looking for new jobs. (Quick recap: Gallup Worker Engagement Index found that roughly 85% of employees are disengaged and 51% of employees are looking for another job.) Recent research adds to that to show that disengagement and satisfaction in work — and the ability to “bring one’s whole self to work” — disproportionately, negatively impacts our colleagues of color.

In one study, researchers found that 38% of our Black colleagues feel it’s never appropriate in the workplace to talk about the bias they experience in life. This makes them twice as likely as those not in this group to experience feelings of isolation, three times as likely to have one foot out the door and be looking for another job, and 13 times as likely to be disengaged in their work.

And this is just as it relates to our colleagues of color. I’m confident that if we looked at findings as they related to other aspects of diversity we’d find similar disheartening results.

The Lovingkindness Lens

I’ve been meditating for a few years now. For those fellow meditators, you’ll be familiar with the Lovingkindness, or metta, meditation. For those less familiar, it basically goes like this: you meditate on phrases like, “May you be safe, be happy, be healthy, live with ease, live with joy,” while focusing first on yourself; then focusing on someone close to you. Next, you focus on someone you know but don’t really know (think of the Starbucks barista you see each morning). Then, you move to someone who really challenges you; and finally, to all beings everywhere.

When I was meditating on these phrases a few months back, I had an epiphany. The Lovingkindness meditation provides an excellent lens to use when seeking to identify blockers for bringing more of oneself to work.

It works like this: how safe is your workplace? Not necessarily physical safety (although that certainly might be part of it) but psychologically safety. How happy are you and your coworkers? How easy is it for you to do your work? Easy as in it doesn’t feel like people keep throwing obstacles in your way at every turn, not that your work isn’t challenging in a good way.

As I meditated on this, I was struck by one of the greatest ironies of the cultural sector. Our sector exists, in large, part to make the world a better, more beautiful and understanding place. And sadly — both anecdotally and backed by research — most people are unfulfilled (and some are downright miserable) doing the work. At what cost are we trying to achieve our charitable missions if we do it by blowing through and burning out our people?

At what cost are we trying to achieve our charitable missions if we do it by blowing through and burning out our people?

When we use Lovingkindness’s “healthy” lens here the shit gets real, fast. How many hours are people working? (And how much work is supposed to be accomplished during that period?) How many people don’t feel like they can step away from their desks for lunch? How many people feel like they can’t take more than a few vacation days a year? And when they do get away, they feel pressure — real or implied — to stay connected to email and voicemails.

Next, let’s use the “work with ease” lens. Again, this doesn’t mean work is easy, it’s that it doesn’t always feel like you’re pushing an ever-larger boulder up an increasingly steep mountain. “All I want to do is send out the annual appeal letters. Why does it feel like I’m participating in some Tough Mudder competition?!” And lastly, does your work bring you joy? If you personally can’t positively answer *that* question, again, I ask at what cost are we doing this work? Life is simply too short.

Some might find it helpful to plot their current positions on a Lovingkindness chart like the one above.

Let’s then ask ourselves, when reflecting on safety, happiness, health, ease, and joy in our workplace, how many of our coworkers can honestly say yes to those things? Is it just the executive director? Or, oh God, maybe not even the executive director. We might not like the results, but burying our head in the sand doesn’t mean that it’s not true. I can’t think of an organization that can check off all of these for every single person. However, (1) that’s no excuse for us not to continually be doing something about it, and (2) this Lovingkindness lens gives us a quick “balance sheet” or snapshot to start using. This snapshot highlights the often amorphous “organizational culture” components so we can pull them apart and begin identifying ways to address them.

The Lovingkindess Lens in Action

The beauty of using the Lovingkindness lens is that it can be applied at the individual, team, and organizational levels. Ask yourself first, do I feel safe in my work and workplace? Why or why not? What does safety at work look and feel like? What would help me to feel safer? Then, am I happy in my work? What would need to change for me to find daily happiness and joy in my work? What part of my work always feels like an unnecessary struggle? (At this point, you might find a job crafting exercise to be quite helpful.)

Sometimes, to bring our whole(ish) selves to work, we need a little help from our friends and colleagues.

Then, take it the next step and ask, who on my team or in my organization might not feel safe? Who might not be happy in their work? Then, before running to them as saying — “Hey, why don’t you feel safe to bring more of yourself to work?” — interrogate your assumptions. Why do you think that? What gives you that impression? If someone doesn’t feel psychologically safe at work, they’re probably not going to give you an honest answer to that question anyways. There likely is work that needs to be done in the organization before you will see progress here. (For more on building psychologically safe workplaces, check out the awesome work by Amy C. Edmondson.)

And lastly, expand this beyond people on staff to consider your board, your volunteers, and those you’re trying to serve. First, how engaged are they in the work? Are they happy with us? Do we help those we serve to be healthy? How easy is it for people to participate in our work? You will likely need to take a few liberties to map these lenses to your organization, but going down the list to articulate “What does safety look like for those we serve?” “How might what we do make it easier for people?” is a helpful starting place.

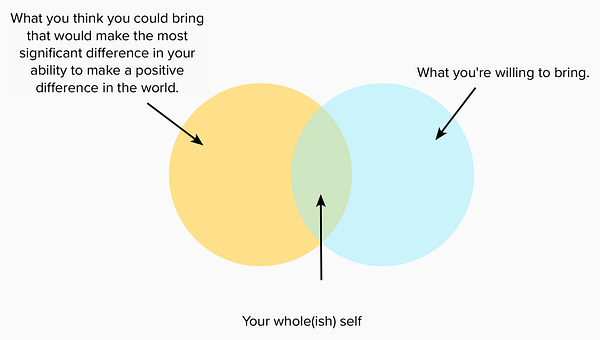

What can I do right now to move towards what I really want?

As we think about the 85% we aim to bring, about safety, happiness, health, ease, and joy — how do we decide what we’re comfortable bringing into a space? And how do we actually do it? Meditating on what to bring will surface things that are personal and bespoke to each of us. We’ll likely discover there’s a Venn diagram of sorts with two components: What you think you could bring that would make the most significant difference in your ability to make a positive difference in the world, and What you’re willing to bring.

We have but one pass at this life. If we’re doing it while overly throttling who we are as humans, to the detriment of ourselves, our ability to achieve our potential and make our dent in the universe, at what cost is this to us truly living? Showing up more fully — especially when it doesn’t inhibit someone else’s humanity — should be a goal we all feel that we can strive towards.

Tim Cynova is an HR and org design consultant, an educator, and podcaster dedicated to dusting off workplaces to (re)center values-based approaches where more people can thrive. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR (SPHR), trained mediator, principal at WSS HR LABS, on faculty at New York’s The New School, Minneapolis College of Art & Design, and Hollyhock Leadership Institute. He has held executive leadership roles in a variety of nonprofits for the better part of the last 20 years, and is also an avid coffee drinker.

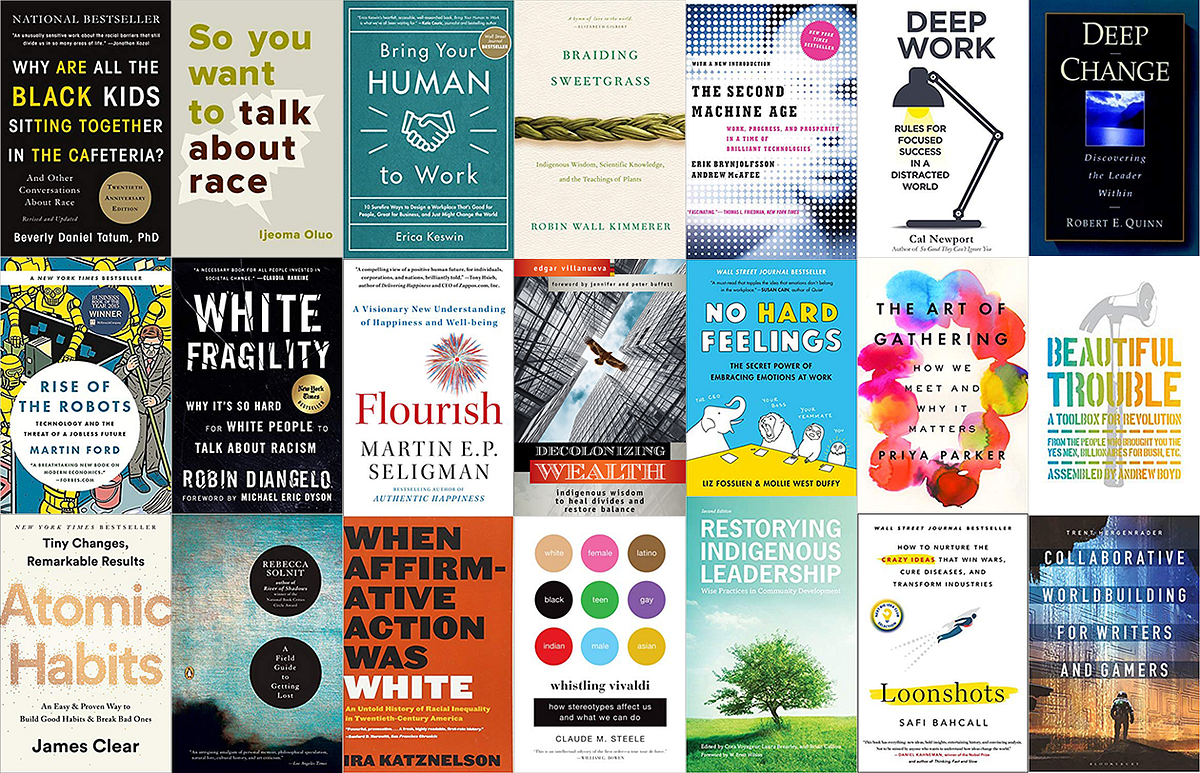

Summer Reading Challenge 2019

Note: The librarian’s last name is Reading. How awesome is that?! (Also note, my mom saved everything.)

By: Tim Cynova // Published: May 24, 2019

Around Memorial Day each year when my sister and I were kids, our parents would take us to the McCollough Branch of the Evansville Public Library. It was that annual rite of passage — the summer reading challenge! We’d select a hefty stack of books, and then hope to God come Labor Day we’d have read enough of them to earn that sweet certificate for a free scoop of Baskin Robbins ice cream.

In the spirit of those early ‘80s summer reading challenges, I’ve pulled together what’s currently on my reading list for the summer. And, if I can complete just four of these books come Labor Day, you better believe I’m headed to Baskin Robbins, or Shake Shack, whichever is closest.

Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants

by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Drawing on her life as an indigenous scientist, and as a woman, Kimmerer shows how other living beings―asters and goldenrod, strawberries and squash, salamanders, algae, and sweetgrass―offer us gifts and lessons, even if we’ve forgotten how to hear their voices. In reflections that range from the creation of Turtle Island to the forces that threaten its flourishing today, she circles toward a central argument: that the awakening of ecological consciousness requires the acknowledgment and celebration of our reciprocal relationship with the rest of the living world. For only when we can hear the languages of other beings will we be capable of understanding the generosity of the earth, and learn to give our own gifts in return.

Restorying Indigenous Leadership: Wise Practices in Community Development

by Cora Voyageur, Laura Brearley, and Brian Calliou

Restorying Indigenous Leadership: Wise Practices in Community Development is a foundational resource of the most recent scholarship on Indigenous leadership. The authors in this anthology share their research through nonfictional narratives, innovative approaches to Indigenous community leadership, and inspiring accounts of success, presenting many models for Indigenous leader development. These engaging stories are followed by a Wise Practices section featuring seven significant contemporary case study summaries. Restorying promotes hope for the future, individual agency, and knowledge of successful community economic development based upon community assets. It is a diverse collection of iterative and future-oriented ways to achieve community growth that acknowledges the centrality of Indigenous culture and identity.

Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance

by Edgar Villanueva

Decolonizing Wealth is a provocative analysis of the dysfunctional colonial dynamics at play in philanthropy and finance. Award-winning philanthropy executive Edgar Villanueva draws from the traditions from the Native way to prescribe the medicine for restoring balance and healing our divides.

Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria?: And Other Conversations About Race

by Beverly Daniel Tatum

Walk into any racially mixed high school and you will see Black, White, and Latino youth clustered in their own groups. Is this self-segregation a problem to address or a coping strategy? Beverly Daniel Tatum, a renowned authority on the psychology of racism, argues that straight talk about our racial identities is essential if we are serious about enabling communication across racial and ethnic divides. These topics have only become more urgent as the national conversation about race is increasingly acrimonious. This fully revised edition is essential reading for anyone seeking to understand the dynamics of race in America.

Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future

by Martin Ford

What are the jobs of the future? How many will there be? And who will have them? As technology continues to accelerate and machines begin taking care of themselves, fewer people will be necessary. Artificial intelligence is already well on its way to making “good jobs” obsolete: many paralegals, journalists, office workers, and even computer programmers are poised to be replaced by robots and smart software. As progress continues, blue and white collar jobs alike will evaporate, squeezing working- and middle-class families ever further. At the same time, households are under assault from exploding costs, especially from the two major industries- education and health care- that, so far, have not been transformed by information technology. The result could well be massive unemployment and inequality as well as the implosion of the consumer economy itself. The past solutions to technological disruption, especially more training and education, aren’t going to work. We must decide, now, whether the future will see broad-based prosperity or catastrophic levels of inequality and economic insecurity. Rise of the Robots is essential reading to understand what accelerating technology means for our economic prospects- not to mention those of our children- as well as for society as a whole.

So You Want to Talk About Race

by Ijeoma Oluo

Ijeoma Oluo offers a hard-hitting but user-friendly examination of race in America. Widespread reporting on aspects of white supremacy — from police brutality to the mass incarceration of African Americans — have made it impossible to ignore the issue of race. Still, it is a difficult subject to talk about. How do you tell your roommate her jokes are racist? Why did your sister-in-law take umbrage when you asked to touch her hair — and how do you make it right? How do you explain white privilege to your white, privileged friend? In So You Want to Talk About Race, Ijeoma Oluo guides readers of all races through subjects ranging from intersectionality and affirmative action to “model minorities” in an attempt to make the seemingly impossible possible: honest conversations about race and racism, and how they infect almost every aspect of American life.

Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World

by Cal Newport

Deep work is the ability to focus without distraction on a cognitively demanding task. It’s a skill that allows you to quickly master complicated information and produce better results in less time. Deep work will make you better at what you do and provide the sense of true fulfillment that comes from craftsmanship. In short, deep work is like a super power in our increasingly competitive twenty-first century economy. And yet, most people have lost the ability to go deep-spending their days instead in a frantic blur of e-mail and social media, not even realizing there’s a better way. A mix of cultural criticism and actionable advice, Deep Work takes the reader on a journey through memorable stories and no-nonsense advice, such as the claim that most serious professionals should quit social media and that you should practice being bored.

When Affirmative Action Was White: An Untold History of Racial Inequality in Twentieth-Century America

by Ira Katznelson

Ira Katznelson fundamentally recasts our understanding of twentieth-century American history and demonstrates that all the key programs passed during the New Deal and Fair Deal era of the 1930s and 1940s were created in a deeply discriminatory manner. Through mechanisms designed by Southern Democrats that specifically excluded maids and farm workers, the gap between black and white people actually widened despite postwar prosperity. In the words of noted historian Eric Foner, “Katznelson’s incisive book should change the terms of debate about affirmative action, and about the last seventy years of American history.”

The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies

by Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee

In The Second Machine Age MIT’s Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee reveal the forces driving the reinvention of our lives and our economy. As the full impact of digital technologies is felt, we will realize immense bounty in the form of dazzling personal technology, advanced infrastructure, and near-boundless access to the cultural items that enrich our lives. Amid this bounty will also be wrenching change. Professions of all kinds―from lawyers to truck drivers―will be forever upended. Companies will be forced to transform or die. Recent economic indicators reflect this shift: fewer people are working, and wages are falling even as productivity and profits soar. Drawing on years of research and up-to-the-minute trends, Brynjolfsson and McAfee identify the best strategies for survival and offer a new path to prosperity.

A Field Guide to Getting Lost

by Rebecca Solnit

Written as a series of autobiographical essays, A Field Guide to Getting Lost draws on emblematic moments and relationships in Rebecca Solnit’s life to explore issues of uncertainty, trust, loss, memory, desire, and place. Solnit is interested in the stories we use to navigate our way through the world, and the places we traverse, from wilderness to cities, in finding ourselves, or losing ourselves. While deeply personal, her own stories link up to larger stories, from captivity narratives of early Americans to the use of the color blue in Renaissance painting, not to mention encounters with tortoises, monks, punk rockers, mountains, deserts, and the movie Vertigo. The result is a distinctive, stimulating voyage of discovery.

No Hard Feelings: The Secret Power of Embracing Emotions at Work

by Liz Fosslien and Mollie West Duffy

The modern workplace can be an emotional minefield, filled with confusing power structures and unwritten rules. We’re expected to be authentic, but not too authentic. Professional, but not stiff. Friendly, but not an oversharer. Easier said than done! As both organizational consultants and regular people, we know what it’s like to experience uncomfortable emotions at work — everything from mild jealousy and insecurity to panic and rage. Ignoring or suppressing what you feel hurts your health and productivity — but so does letting your emotions run wild. Our goal in this book is to teach you how to figure out which emotions to toss, which to keep to yourself, and which to express in order to be both happier and more effective.

Loonshots: How to Nurture the Crazy Ideas That Win Wars, Cure Diseases, and Transform Industries

by Safi Bahcall

Loonshots reveals a surprising new way of thinking about the mysteries of group behavior that challenges everything we thought we knew about nurturing radical breakthroughs. Drawing on the science of “phase transitions,” Bahcall shows why teams, companies, or any group with a mission will suddenly change from embracing wild new ideas to rigidly rejecting them. Using examples that range from the spread of fires in forests to the hunt for terrorists online, and stories of thieves and geniuses and kings, Bahcall shows how this new kind of science helps us understand the behavior of companies and the fate of empires. Loonshots distills these insights into lessons for creatives, entrepreneurs, and visionaries everywhere.

Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do

by Claude M. Steele

Claude Steele shares the experiments and studies that show, again and again, that exposing subjects to stereotypes impairs their performance in the area affected by the stereotype. Steele’s conclusions shed new light on a host of American social phenomena, from the racial and gender gaps in standardized test scores to the belief in the superior athletic prowess of black men. Steele explicates the dilemmas that arise in every American’s life around issues of identity, from the white student whose grades drop steadily in his African American Studies class to the female engineering students deciding whether or not to attend predominantly male professional conferences. Whistling Vivaldi offers insight into how we form our senses of identity and ultimately lays out a plan for mitigating the negative effects of “stereotype threat” and reshaping American identities.

Bring Your Human to Work: 10 Surefire Ways to Design a Workplace That Is Good for People, Great for Business, and Just Might Change the World

by Erica Keswin

As human beings, we are built to connect and form relationships. So, it should be no surprise that relationships must also translate into the workplace, where we spend most of our time. Companies that recognize this will retain the most productive, creative, and loyal employees, and invariably seize the competitive edge. The most successful leaders are those who actively form quality relationships with their employees, who honor fundamental human qualities―authenticity, openness, and basic politeness―and apply them day in and day out. Paying attention and genuinely caring about the effects people have on one another other is key to developing a winning culture where people perform at the top of their game and want to work.

Atomic Habits: An Easy & Proven Way to Build Good Habits & Break Bad Ones

by James Clear

Atomic Habits offers a proven framework for improving and will teach you exactly how to form good habits, break bad ones, and master the tiny behaviors that lead to remarkable results. Atomic Habits will reshape the way you think about progress and success, and give you the tools and strategies you need to transform your habits — whether you are a team looking to win a championship, an organization hoping to redefine an industry, or simply an individual who wishes to quit smoking, lose weight, reduce stress, or achieve any other goal.

White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism

by Robin DiAngelo

In this “vital, necessary, and beautiful book” (Michael Eric Dyson), antiracist educator Robin DiAngelo deftly illuminates the phenomenon of white fragility and “allows us to understand racism as a practice not restricted to ‘bad people’ (Claudia Rankine). Referring to the defensive moves that white people make when challenged racially, white fragility is characterized by emotions such as anger, fear, and guilt, and by behaviors including argumentation and silence. These behaviors, in turn, function to reinstate white racial equilibrium and prevent any meaningful cross-racial dialogue. In this in-depth exploration, DiAngelo examines how white fragility develops, how it protects racial inequality, and what we can do to engage more constructively.

Deep Change: Discovering the Leader Within

by Robert E. Quinn

Don’t let your company kill you! Open this book at your own risk. It contains ideas that may lead to a profound self-awakening. An introspective journey for those in the trenches of today’s modern organizations, Deep Change is a survival manual for finding our own internal leadership power. By helping us learn new ways of thinking and behaving, it shows how we can transform ourselves from victims to powerful agents of change. And for anyone who yearns to be an internally driven leader, to motivate the people around them, and return to a satisfying work life, Deep Change holds the key.

Beautiful Trouble: A Toolbox for Revolution

by Andrew Boyd and Dave Oswald Mitchell

Beautiful Trouble brings together dozens of seasoned artists and activists from around the world to distill their best practices into a toolbox for creative action. Sophisticated enough for veteran activists, accessible enough for newbies, this compendium of troublemaking wisdom is a must-have for aspiring changemakers. Showcasing the synergies between artistic imagination and shrewd political strategy, Beautiful Trouble is for everyone who longs for a more beautiful, more just, more livable world — and wants to know how to get there.

Collaborative Worldbuilding for Writers and Gamers

by Trent Hergenrader

The digital technologies of the 21st century are reshaping how we experience storytelling. More than ever before, storylines from the world’s most popular narratives cross from the pages of books to the movie theatre, to our television screens and in comic books series. Plots intersect and intertwine, allowing audiences many different entry points to the narratives. In this sometimes bewildering array of stories across media, one thing binds them together: their large-scale fictional world. Collaborative Worldbuilding for Writers and Gamers describes how writers can co-create vast worlds for use as common settings for their own stories. Using the worlds of Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, A Game of Thrones, and Dungeons & Dragons as models, this book guides readers through a step-by-step process of building sprawling fictional worlds complete with competing social forces that have complex histories and yet are always evolving. It also shows readers how to populate a catalog with hundreds of unique people, places, and things that grow organically from their world, which become a rich repository of story making potential.

The Art of Gathering: How We Meet and Why It Matters

by Priya Parker

In The Art of Gathering, Priya Parker argues that the gatherings in our lives are lackluster and unproductive — which they don’t have to be. We rely too much on routine and the conventions of gatherings when we should focus on distinctiveness and the people involved. At a time when coming together is more important than ever, Parker sets forth a human-centered approach to gathering that will help everyone create meaningful, memorable experiences, large and small, for work and for play. The result is a book that’s both journey and guide, full of exciting ideas with real-world applications. The Art of Gathering will forever alter the way you look at your next meeting, industry conference, dinner party, and backyard barbecue — and how you host and attend them.

Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being

by Martin E.P. Seligman

Flourish builds on Seligman’s game-changing work on optimism, motivation, and character to show how to get the most out of life, unveiling an electrifying new theory of what makes a good life — for individuals, for communities, and for nations. In a fascinating evolution of thought and practice, Flourish refines what Positive Psychology is all about. With interactive exercises to help readers explore their own attitudes and aims, Flourish is a watershed in the understanding of happiness as well as a tool for getting the most out of life.

So, what’s on your summer reading list?

Tim Cynova is a leader, HR consultant, and educator dedicated to co-creating anti-racist and anti-oppressive workplaces through using human-centered organizational design. He is a certified Senior Professional in HR, trained mediator, principal at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck., on faculty at New York’s The New School and Canada’s Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity, and for the past twelve years served as COO and then Co-CEO of the largest association of artists, creatives, and makers in the U.S.

Opportunities to Live Our Anti-Racism, Anti-Oppression Values

By: Tim Cynova // Published: January 8, 2019

[This time of year brings a whole host of looking back, looking forward pieces. Instead of a round-up of the top books or movies, or predictions about what’s to come in 2019, I thought it might be a good time to check in on our anti-racism, anti-oppression journey at Fractured Atlas.]

A number of years ago when Fractured Atlas was beginning in earnest our journey towards becoming an anti-racist, anti-oppressive organization I asked someone working in the space if they could point me in the direction of case studies about other companies with similar complexities to ours who were doing the work well. (When embarking on something new, I often scan the space to see what kind of learning is available that I can leverage and then iterate on in our own work.) The person essentially said, nope, they couldn’t think of any, but that people were watching Fractured Atlas as we embarked on this journey and would be interested to see how we approached it. That was about four years ago.

Lauren, Lisa, and I at TCG’s CultureMakers gathering. (Photo: Ryan Bourque)

Increasingly in recent months, my Fractured Atlas colleagues Nicola Carpenter, Courtney Harge, Lauren Ruffin, Jillian Wright, our Board member Lisa Yancey, and I have had opportunities to chat with awesome people around the country about where we are in our organizational journey, and share ideas and experiences around the “how” of operationalizing commitments to creating anti-racist, anti-oppressive (ARAO) teams and organizations.

It’s not uncommon for us to meet with those in predominantly white organizations and find people wanting to do the work, but not sure exactly how to approach it. In the absence of a template, clear path forward, or “buy in” from their board of directors, they remain stuck. And in doing this work, it quickly becomes evident that we’re either moving forward, or we’re falling behind.

There is no neutral. Racism and oppression don’t take days off.

Specific Things We’ve Been Doing

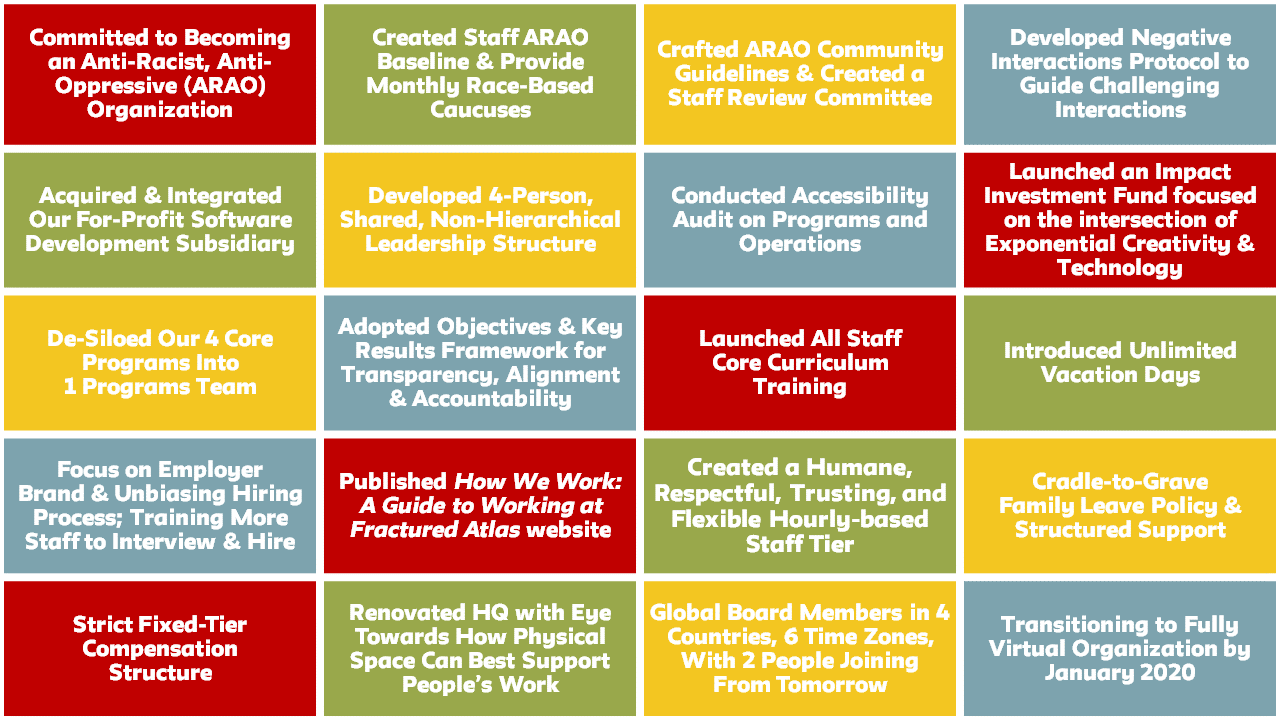

We created the image below as a kind of snapshot of what’s happened over the past few years during our ARAO journey at Fractured Atlas. The graphic (and duplicate list below) includes things we’ve explored and implemented to support the creation of a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable workplace, and some significant milestones that have occurred along the way. The image is the result of a quick, almost stream-of-consciousness round up of the many things we’ve experienced at Fractured Atlas, with many happening in the past two years.

A snapshot of opportunities from the past few years that have allowed us to live our ARAO values at Fractured Atlas. (Not necessarily listed in chronological order.)

Committed to becoming an anti-racist, anti-oppressive (ARAO) organization

Created staff ARAO baseline & provide monthly race-based caucuses

Crafted ARAO Community Guidelines & created a staff review committee

Developed Negative Interactions Protocol to guide challenging interactions

Acquired & integrated our for-profit software development subsidiary

Developed four-person, shared, non-hierarchical leadership structure

Founder & CEO departed after 20 years

Launched an impact investment fund focused on the intersection of exponential creativity & technology

De-siloed our four core programs into one Programs team

Adopted Objectives & Key Results (OKR) framework for increased transparency, alignment & accountability

Launched all staff core curriculum training

Introduced unlimited vacation days

Focused on employer brand & unbiasing hiring process; training more staff to interview & hire

Published How We Work: A Guide to Working at Fractured Atlas

Created a humane, respectful, trusting, and flexible hourly-based staff tier

Cradle-to-grave family leave policy & structured support

Strict fixed-tier compensation structure

Renovated HQ with eye towards how physical space can best support people’s work

Global Board with members in 4 countries, 6 time zones, and 2 people joining from tomorrow

Transitioning to be fully virtual organization by January 2020

Oh, almost forgot! We launched a companion site for this work at Work. Shouldn’t. Suck.

The list is by no means exhaustive. It’s been an incredibly busy couple of years filled with exploration, change, and iteration on many fronts. (Here is a round up of changes we experienced in simply one year alone.) This list also largely omits numerous changes in our programs and services, as well as developments in our software and technology infrastructure — both of which have experienced an entire grid of activity in their own rights — in favor of focusing more on ones firmly intersecting our People Operations work.

What If? How Might We?

Each tile on the grid above reflects opportunities where we asked ourselves a series of questions that usually began with a “What if?” or “How might we?” How might we better live our anti-racism, anti-oppression principles to serve our amazing members? How might we craft an organization that is more diverse, more inclusive, and more equitable as we approach this new thing? How might we create a workplace where more of our coworkers can thrive and make their dents in the universe?

Then we got more granular: What if we approached designing an organizational leadership structure that was more reflective of our ARAO values rather than how conventional “wisdom” suggests organization to structure hierarchically? How might [insert item] be an opportunity for us to better reflect our ARAO commitment, support people, and move our organization forward? If we all don’t live and work in the same city, how might we build a unified organizational culture, rather than one that varies depending on where someone is located?

Each item in the grid could have its own blog post, if not a book, delving into the how, the why, the stumbling blocks, and the lessons learned. Fortunately, we *have* written about some of these efforts here, here, here, here, and here. (And have more pieces in development.) Other items we dive into more deeply during our Work. Shouldn’t. Suck. bootcamps, HR Hours, and brown bag lunch chats with various organizations.

Has It Made Any Difference?

Looking at staff composition is one way — but certainly not the *only* way — of seeing how this work, and our journey, has impacted Fractured Atlas. Given that when we began this work we were a white-led organization with only one or two people of color on staff; we primarily worked from one office in New York City; and, we only had white men on our software development team, personnel metrics became a helpful proxy. Below is a snapshot of how those demographics changed over a five-year period.

A few of the metrics we tracked to see how our staff composition changed over 5 years.

Moving Forward in Ambiguity

The journey certainly hasn’t been without challenges, as any foray involving change is certain to include. (I wrote an entire piece about the psychological impacts of change here, and we’ve ticked off numerous instances of each during this journey.) We have and continue to struggle in places, and encountered unexpected hiccups in others. We made the best decisions we could at the time and then, importantly, iterated when things didn’t work out as we had hoped. This process continues to this day because, once on this journey, the work never ends.

There’s still no reliable template that I’ve found to do the work of dismantling racism and oppression in the workplace, which often leads to expressions of disappointment when people ask. It all depends really. It depends on where you are as a team and organization. It depends on your available resources. It depends most of all on your joint commitment — staff and board — to do the work, especially when it seems hardest and like you’re not making any progress. We move forward in ambiguity, an old friend of mine used to say, and we keep moving.

Because this work, and world, are ever evolving, we at Fractured Atlas couldn’t even follow the path we took if we were to do it all over again. That’s a liberating thought, though. The work is bespoke. All of us can use our creativity — wherever we find ourselves in our organizations — to move it forward. Simply reflecting on this question can yield helpful ideas: How might the decisions I make right now about [this thing] move us towards a more diverse, inclusive, and/or equitable team and organization? We all have agency, even if it might not initially seem so.

Ideas to Explore

Creating a negative interactions protocol and starting monthly race-based caucusing are great ways to move the work forward. But, depending on where you and your organization are in the journey, there might be other things you want to explore first. Might I suggest a few items for your consideration?

Here are a few ideas:

Begin introducing yourself using your gender pronouns, and ask others theirs. List yours in your bio or email signature.

Start a staff book club to explore new ideas and skill development. Might I suggest something from the lists here, here, and here.

Bring more new ideas and perspectives to your work from outside of your sector through a regular Visiting Professionals Series. #ProTip: Ask your Board chair to be the inaugural guest. Or, ask someone from a group who’s doing diversity, inclusion, and/or equity work to come and share their journey.

Strengthen board/staff connections and understanding by having an annual board/staff reception before a board meeting. It doesn’t need to be fancy, the sheer act of getting people together will be appreciated by those in attendance.

Take a few minutes to complete the Core Values Exercise Patrick Lencioni details in The Advantage. Why?

Learn more about how to create high-performing teams and organizations by listening to Adam Grant’s Work/Life podcast.

Are you a White person? Listen to Scene on Radio’s Seeing White series and use the study guide resource to discuss it with other white people. Or explore similar resources.